History of Science and Technology in Islam

THE ARABIC ORIGIN OF THE SUMMA AND GEBER LATIN WORKS:

A REFUTATION OF BERTHELOT, RUSKA AND NEWMAN ON THE BASIS OF ARABIC SOURCES

AHMAD Y. AL-HASSAN[1]

ABSTRACT

This paper presents a reassessment of the Geber Problem on the basis of

research into the extant Arabic works of Jābir ibn Ḥayyān and other

Arabic works that incorporated his ideas. Part I discusses the

hypotheses of Marcelin Berthelot which heralded the problem and texts

from the Summa and Arabic

sources are compared, and thus the Arabic identity of the Summa

is confirmed.

Part II refutes the assumptions of Julius Ruska about a Latin author for

part of the Liber Geberis De

Investigatione Perfectionis Magisterii of the Riccardiana

manuscript, and for the Summa. It follows that all the

assumptions of William Newman that were built on Ruska’s speculations,

about a previously unknown compiler called Paul of Taranto as the author

of the Summa are baseless.

INTRODUCTION

“Geber” was the name ascribed to the author of a series of alchemical

treatises which began to appear in the Latin West in the middle of the

13th century. These treatises included the

Summa Perfectionis Magesterii;

De Investigatione Perfectionis

[2];

De Inventione Veritatis; Liber Fornacum

and

Testamentum,

which were usually printed together between the 15th and 17th

centuries. These were known

until the nineteenth century to be translations of works originally

written in Arabic by Jābir ibn Ḥayyān.[3]

His name, in the Latin form “Geber”, became widely celebrated. The

Summa was so successful that,

according to George Sarton, it became the main chemical textbook in

medieval

This attribution to Jabir was not challenged until the end of the 19th

century. In1893, Marcelin Berthelot claimed in his work

La Chimie au Moyen Âge

that these treatises had been written by Latin authors who

would have used Jābir’s name in order to facilitate the diffusion of

their own works. Berthelot was a noted scientist and a public figure,

and as a high official he was most influential in

However, several eminent historians of chemistry and alchemy raised

serious objections to Berthelot’s assumptions. The earliest appeared in

1905 by Henry E. Stapleton,[8]

while the largest and most consistent objections were raised by Eric J.

Holmyard in a series of papers published between 1922 and 1928.[9]

James .R. Partington sided with Holmyard,[10]

whereas Lynn Thorndike would further question Berthelot’s accuracy and

judgments.[11]

Notwithstanding, in 1935, Julius Ruska attributed the authorship of a

part of Liber Geberis De

Investigatione Perfectionis Magisterii of the Riccardiana manuscript

[12]

to a Latin author,[13]

who would be also the author of the Summa.

In 1986, William Newman adopted Ruska’s assumptions and he attributed

the Summa to a previously unknown writer by the name of Paul of

Taranto.[14]

In this way, although the “Geber Problem” is more than one century old

and in spite of the definitive judgments by Holmyard and other scholars,

the assumptions of Berthelot, Ruska and Newman are still adopted

uncritically by Western historians of alchemy.

We have dealt with some of Berthelot’s assumptions elsewhere and will

not be repeated here,[15]

thus in Part I of the present paper we make a brief summary of our

refutation of these assumptions, and continue with a discussion of the

remaining ones.

In Part II, we dispute Ruska’s speculations in his study of the DIP

and his unfounded assumption that a Latin author wrote part of it. We

shall discuss also William Newman’s assumptions which were built on

Ruska’s speculations and which culminated in the conjecture that an

unknown compiler called Paul of Taranto was the author of the

Summa.

In this way, we hope to contribute in bringing to light the deliberate

errors on which the early history of Latin alchemy is built.

I

REFUTATION OF MARCELIN BERTHELOT’S ASSUMPTIONS

Berthelot’s main claims for Latin authors of Geber’s works can be

summarized in the following assumptions[16]:

1. The treatises carrying Jābir’s name were written by Latin authors,

who attributed their work to Jābir due to his high standing in the West.

2. There are no Arabic originals for these same works.

3. The style in the Arabic works by Jābir is vague and allegoric.

4. The style of the Summa

recalls the style of the Schoolmen.

5. The Summa is devoid of

Muslim expressions, which are extravagant in the Arabic texts of Jābir.

6. The Summa contains an

account of the arguments against transmutation, which is not existent in

Arabic works.

7. The Arabic works of Jābir do not contain practical recipes for the

preparation of materials.

8. The minor Latin works bearing Geber’s name mention more modern

materials, such as saltpeter, salt of tartar, rock alum and feather

alum, as well as the preparation of nitric acid, which are absent in the

Arabic works of Jābir.

9. The Arabic works do not mention the sulphur-mercury theory of the

generation of metals, nor the three principles in metals – sulphur,

arsenic and mercury.

We shall now discuss these assumptions in the same order:

1.

Jābir’s Hypothetical High Standing in the West

Before the translation of Arabic works into Latin, alchemy was unknown

in the West. Robert of Chester finished in 1144 the first translation

from Arabic of a book on alchemy –

Liber de Compositione Alchimiae.

In the preface he states, “Since what Alchymia is, and what its

composition is, your Latin world does not yet know, I will explain in

this present book”.[17]

Between this and 1300, some major Arabic alchemical works were

translated into Latin, including

Tabula Smaragdina, Turba

Philosophorum, The Secret of Creation of Bālīnās,

De Perfecto Magisterio,

attributed to Aristotle, De

Aluminibus et Salibus and the

Liber lumen luminum by al-Rāzī, parts of

Kitāb al Sabʿīn (The Book of

Seventy) by Jābir,[18]

and possibly De anima in arte alchimiae attributed to Ibn Sīnā

(Avicenna).[19]

The “Book of Seventy” that was partially translated by Gerard of Cremona

in the 12th century, does not carry Jābir’s name.[20]

Most Latin authors believed it was a work by al-Rāzī, and the actual

author remained unknown until the end of the 19th century.[21]

Other than this, we do not know of any other work by Jābir which was

translated into Latin before the middle of the 13th century.

The alchemical works of the thirteenth century that were written by

Latin authors such as the works of Michael Scot (1175-1233) and of

Vincent de Beauvais who wrote his speculum works between 1220 and

1244, quote numerous Arabic authors, but Jābir (Geber) is not among

them.[22]

For Albertus Magnus, the only authority in alchemy was Ibn Sīnā, whereas

Roger Bacon did not mention Geber (Jābir) also although he was

acquainted with alchemy through Latin translations of Arabic works.[23]

Therefore, as Jābir was not known in the West in the 13th

century, there is no reason to suppose that any Latin author would

attribute his work to him. On the other hand, according to Roger Bacon’s

appraisal of the status of alchemy at the end of the century, it would

be highly impossible for a Latin writer to compose such a considerable

and mature corpus of alchemical knowledge: “But

there is another science which is about the generation of things from

the elements […] of which we

have nothing in the books of Aristotle; nor do

natural philosophers know of

these things, nor the whole Latin crowd of Latin writers.”

[24]

Translator of Liber fornacum

Furthermore, there are frequent cross-references between the

Summa and the

Liber fornacum. It was

possible to establish that the latter is a translation form the Arabic,

and we currently know the name of the translator and the place and date

of the translation.[25]

This fact is of utmost importance and it is sufficient in itself to

demolish the assumptions of Latin authors for Jabir’s Latin works. It is

indeed bewildering why

historians of chemistry and science kept silent about it.

2-

Lack of Arabic Originals

We have surveyed all the extant dated Arabic MSS attributed to Jābir.[26]

The oldest ones (2%) do not go earlier than the 12th century.

This is to say, all MSS by Jābir which preceded the 12th

century have perished and, among them, most probably also the ones used

by translators. All Arabic MSS were written on paper which deteriorates

with the passage of time and the factors of the environment, and not on

parchment which was the only writing material in the West before the

advent of printing.

On the other hand, we should remember that the Arabic originals of many

significant Latin translations of Arabic scientific and philosophic

works were also lost, surviving exclusively in Latin or Hebrew.[27]

3- The Allegorical Style of Jābir’s Arabic Works

Jābir’s alchemical and chemical works may be classified in two groups.

The first includes writings on the Art of alchemy, while the second

consists of numerous treatises on practical alchemy and industrial

chemistry.[28]

Berthelot selected for his analysis works belonging exclusively to the

first group. This was already noticed by Holmyard: “[Berthelot]

deliberately wanted to underrate Jābir […], the choice of Jābir’s works

made by Berthelot is entirely misleading.”

[29]

4- The Style of the Summa Recalls that of the Schoolmen

Jābir was a philosopher and according to al-Fihrist,

[30]

he wrote numerous works on philosophy. More recently, Paul Kraus was

able to list 23 titles for Jabir on philosophy, among which several deal

with logic.[31]

In several works of Jābir there are arguments where he describes two

opposite points of view and employs logic to arrive at a right

conclusion.[32]

Thus, Jābir was well versed in the tools later employed by the

Schoolmen.[33]

5. Muslim Expressions

According to Holmyard, “It is here that Berthelot’s ignorance of Arabic

led him astray. As a matter of fact, the

Summa is full of Arabic

phrases and turns of speech, and so are the other Latin works”.[34]

Our study of the Summa confirms Holmyard’s assertion.[35]

Indeed, it retained several Islamic expressions of praise to God, mostly

of Qur’anic origin. Furthermore, there are also well known Arabic

sayings. For instance in De

Investigatione, “Contraries set near each other are the more

manifest”

وبضدها تتميز الاشياء;

“Haste is from the Devil’s side”

العجلة من الشيطان.[36]

6. Arguments for and Against Transmutation

Debates regarding the validity of

al- Ṣanʿa (The Art) and

the possibility of the transmutation of base metals into gold began with

the inception of Arabic alchemy itself.[37]

Throughout Jābir’s works references are found to the need to defend the

Art against those who denied it. Jābir systematically warned his readers

to be aware of them and gave instructions on how to confront them.[38]

More specifically, he wrote two treatises devoted to the subject:

Al-Burhān wa ithbāt al- Ṣanʿa

(The Proof and the Verification of the Art)

[39]

and Kitāb al-thiqa bi

ṣiḥḥat al-‘ilm (The

Book of Confidence in the Truth of Science)[40].

After Jābir, the debate continued unabated. Al-Jāḥiẓ (ca.781-868) was

not convinced of the validity of the Art[41]

and al-Kindī (ca.801-873) wrote

Kitāb ibṭāl da’wā al-muddaʿīn

ṣanʿat

al-dhahab wa al fiḍḍa min ghayr ma’ādinihā (A Refutation of Those

Who Pretend to be Able to Win Gold and Silver Otherwise than from

7. Recipes for the Preparation of Materials

Berthelot assumed that Jabir’s works are devoid of recipes for the

preparation of materials. A survey of 59 MSS by Jābir on practical

alchemy shows the description of large umbers of recipes.[46]

There is a whole treatise of recipes which is

Kitāb

al-durra al-maknūna

(The Book of the Hidden Pearl),[47]

which contains dozens of recipes on the colouring of glass, the

manufacture of artificial pearls and improving their colour, and several

other industrial products.[48]

Also, Kitāb

al- Khawāṣṣ al

kabīr

(The Great Book of

Properties),[49]

contains many chemical and industrial chemical

recipes[50]

on the manufacture and annealing of steel,[51]

the de-salination of sea and brackish water by ultra filtration,[52]

the

manufacture of zunjufr

(cinnabar)

[53],

the colouring of glass,[54]

the manufacture of pearls,

[55]

several recipes on cosmetics (removing unwanted hair,[56]

dying of hair into yellow gold

[57]

and dying the hands of maidens with various colours),[58]

on varnishes and paints including waterproofing,

[59]

making inks of various colours,

[60]

and several other industrial products. The other books of

Jābir contain

also many recipes for the preparation of most of the chemical materials

that were known, which include for example the making of salt of alkali

(milḥ al-qalī),

[61]

the refining of tin

(raṣāṣ

qal’ī)

[62]

of

iron [63]

and the other metals.

8. Modern Materials

The large number of recipes described in the MSS declared above, mention

all materials known to alchemists and chemists until the end of the

Middle Ages. We have dealt with Berthelot’s assertion that saltpeter and

nitric acid were first known after the 13th century

elsewhere.[64]

There it was shown that saltpeter was known under various names since

the beginnings of Arabic alchemy and chemistry, while several recipes

for nitric acid are given in

Jābir’s

Arabic works as well as in other Arabic treatises before the 13th

century.

9. Theories of Alchemy in the Summa and in Arabic Works

Contrary to Berthelot’s views, the sulphur-mercury theory and the theory

of three principles of metals – sulphur, arsenic, and mercury – arrived

to the Latin West via Arabic translations. The sulphur-mercury theory

was basic to Arabic alchemy. We shall discuss both theories as they were

expounded in Arabic works and compare them with the texts of the

Summa, together with other

theories of Arabic alchemy.

a- The Two Exhalations Theory

In Arabic alchemy, smoke (dukhān)

and vapour (bukhār)

were considered to be the origin of metals and stones and were equated

to sulphur and mercury.[65]

Although the smoke-vapour notion had started with Aristotle,[66]

the full account of their role in the generation of metals and the

relation to the sulphur-mercury theory was first given in

Bālīnās’

Kitāb

sirr

al khalīqah

(Book of the Secret of Creation) or

Kitāb

al-‘ilal

(The

Book of Causes

).

[67]

According to Paul Kraus,

Jābir

drew heavily from this source in his own works, including the two

exhalations theory and the sulphur-mercury theory.[68]

Bālīnās’

“Book of the Secret of Creation”

was translated into Latin in the 12th century by Hugh of

Santalla, who stayed in Tarazona from 1145 o 1151.

We compared the chapter dealing with the generation of metals in Françoise

Hudry’s edition of Hugo of Santalla’s

Latin translation with the corresponding chapter in Ursula Weisser’s

edition of Kitab sirr al

khalīqah,

[69]

and found them to be similar (Appendix 1). From this, it is evident that

the two exhalations theory of the generation of metals and the sulphur-mercury

theory were available in Latin since the middle of the 12th

century and not at the end of the 13th century as Berthelot

had claimed.

Vincent of Beauvais was acquainted with these theories. Lynn Thorndike

asserts that in Speculum

Doctrinale,

“…everything has an occult quality opposed to its natural one; that four

spirits, mercury, sulphur, arsenic and sal ammoniac, and six metals,

gold, silver, copper, tin, lead and iron are generated in the bowels of

the earth; and that the metals are generated by mercury and sulphur.”

[70]

For this reason Thorndike did not accept Berthelot’s assertion that

these basic theories of alchemy were not known in the West until the

Summa had appeared at the end

of the 13th century. Although Thorndike did not question the

authenticity of

Comparison of the Exhalation Theory in Arabic alchemy and the

Summa

The Arabic text for the exhalation theory and the text of the Summa,

are reproduced in Appendix 2. An attentive reading of the Arabic and the

Summa accounts shows them to

be remarkably similar. Both assert that the metallic bodies cannot be

generated from mercury and sulphur in their natural form (Summa)

or in their coagulated form (Arabic). Both argue that natural sulphur

and mercury cannot be found together in the same mine, but that each one

is to be located in its own separate mine. For this reason, they should

be used in the form of an earthy substance (Summa)

or non-coagulated form (Arabic). Metallic bodies are, thus, formed from

a double fume (Summa) or from

vapour and smoke (Arabic).

This close resemblance of the Summa’s text to the Arabic one

refutes Newman’s assumption that “the theory probably occurred first in

the TP, from whence it was

transferred to the Summa”.[73]

Indeed the

TP’’s account itself is also

taken from an Arabic origin[74].

It is quite obvious, therefore, that the account in the Summa for

the exhalation theory is an Arabic one. This leads us to two

corollaries, one regarding the corpuscular theory, and the other

regarding the mercury alone theory.

b- The “Corpuscular Theory”

An assumed “corpuscular theory” was given great publicity by Newman and

it was the main theme of at least one academic conference, the

proceedings of which were lavishly published by Brill of Leiden.[75]

Newman thought that this theory was first propounded in the Summa

and that it was a theory of Paul of Taranto[76].

However, this so-called “corpuscular theory” in the

Summa is nothing but the same

two exhalations theory already discussed. Nonetheless, it is worthy to

remind that this Aristotelian concept had been elaborated by Bālīnās in

his “Book of the Secret of Creation”, which was one of the basic

sources for Jābirian alchemy, and the basis of the sulphur-mercury

theory.

To give special prominence to the alleged singularity of this theory,

Newman chose the word corpscule

to translate the Latin pars,

in the stead of part as

Russell had done.[77]

Nevertheless, the words ”pars”, “part” and “corpscule” are translations

of the same Arabic word juz’.

Newman also attached particular significance to the degree of “packing”

of the “parts” of a metal, as such “packing” affected its weight and its

proximity to perfection.[78]

This same “packing” (talzīz

or tarzīz) of the “parts” (ajzā’,

singular: juz’’) of a

metallic body occurs frequently in Arabic alchemy within the context of

the two exhalations theory. A small selection from Arabic texts is

presented below in order to show how Newman’s “corpuscular theory” is an

old concept in Arabic alchemy.

Bālīnās

-

On gold: “And it became heavy ‘razīn’

because its parts entered into each other”.[79]

-

On mercury: “It is heavy in weight and its parts entered into each

other”.[80]

Jābir

-

On gold: “Its parts entered into each other in an intermingling that

cannot be separated and it works with them all.”[81]

-

On silver: “To become gold, silver needs two things: the packing of its

parts (tarzīz) and tinting.”[82]

Al-

Jildakī

-

On metallic bodies in general: “A condition for the removal of ailment

from a metallic body is that its parts should be packed so that it

acquires weightiness instead of lightness.”[83]

c- The “Mercury Alone” Theory

The emphasis on mercury, rather than sulphur, is based on old knowledge

in Arabic alchemy. From a single sentence in the Summa, Newman

assumed that this idea would have begun in the 13th-14th

century. This sentence reads: “And if you can perfect by

Argentvive only you will be

the Searcher out of a most

precious Perfection; and of the

Perfection of that which overcomes the

Work of Nature.”[84]

This sentence appears in the

Summa’s chapter on the nature of Venus or copper. The full paragraph

reads:

“Hence it is manifest that those

Bodies are of greater

Perfection which contain more of

Argentvive; but what contain

less, of less Perfection.

Therefore study in all your Works

that Argentvive may excel in

the Commixtion. And if you

can perfect by Argentvive

only you will be the Searcher

out of a most precious Perfection;

and of Perfection of that

which overcomes the Work of

Nature. For you may cleanse it most inwardly to which

Mundification Nature cannot

reach. But the Probation of

this viz. that those

Bodies which contain a

greater Quantity of

Argentvive are of greater

Perfection is their easie

Reception of Argentvive.

For We see Bodies of

Perfection amicably to

embrace Argentvive.”

This text is recommending mercury “if you can”. But in the

Summa itself there are

recipes prescribing other ingredients besides mercury. For instance, one

recipe is for the solar medicine of the third order which transmutes

silver into gold; here sulphur is the essential ingredient.[85]

The importance of mercury as the matter of metals was repeatedly stated

in the Arabic alchemical literature and it recurred in the

Summa and also in the works

of the fourteenth century Latin alchemists, and it is in conformity with

the sulphur-mercury theory.[86]

Concerning the Arabic sources, the examples below will suffice:

Bālīnās

“I say that the origin of all melting bodies is mercury (…) Mercury is

the origin of melting bodies and it is the first one among them and they

were formed from it.”[87]

Jābir

“Mercury is the origin of melting bodies and it is their material and

first object, like the sperm for animals or the seed for plants.”[88]

Jābir’s comparison of mercury to sperm was repeated by Arnold of

Villanova[89]

and John Dustin but does not occur in the

Summa

[90].

d- The

and the Composition of Metals.

Berthelot assumed that the Arabic works of Jābir did not mention the

sulphur-mercury theory.

Later, Newman assumed that a text in the

TP on the differences in the

constitution of metals is unique and is one of two main proofs for the

relationship between the TP and the

Summa. However, the account

for differences in the composition of metals is part of the sulphur-mercury

theory and is an essential concept in Arabic alchemy. Indeed, it is the

basis on which the whole idea of transmutation is built. Gold was the

perfect metal, followed by silver. The four remaining metals – copper,

iron, tin and lead – were defective. The aim of alchemy was, precisely,

to treat the defective metals in order to be brought back to the ideal

composition of gold. Arabic alchemy texts give accounts of the

differences among the metals in one form or another.[91]

The first account is found in the Book of the Secret of Creation

of Bālīnās. Several other accounts are present in Jābir’s works as well

as in the works of other alchemists.

In the case of gold, the texts quoted below agree that mercury is its

main constituent, while sulphur should be pure and non-combustible.

Regarding other metals, the accounts by Jābir and the

Summa are quite similar, with

insignificant variations. Newman acknowledged that this part of alchemy

was common knowledge in the 13th century. Nevertheless, he

also believed that the Summa

and the TP contained unique

information regarding the fixedness (non volatility) and the indication

of the amounts.[92]

A close look at the Arabic sources reveals that such information was not

unique.

Jābir

“Mercury is the origin of metals; it is their matter and their principal

constituent.”[93]

“And we shall say also that all metallic bodies in their essences are

mercury that was set (coagulated) by means of the sulphur of the mine

that has risen to it with the vapours of the earth. And they (i.e. the

bodies) have differed because of the differences in their properties;

and their properties differed because of the differences in their

sulphurs. The differences in their sulphurs are caused by the

differences in their earths and in their positions in relation to the

heat that reaches them from the sun as it oscillates in its orbit. And

the finest of those sulphurs, the purest and the most temperate was the

golden sulphur and for this reason mercury was coagulated with it firmly

and temperately; and because of this temperance it resisted fire and it

stood firm and fire was not able to burn it in the same way as it burns

other bodies.”[94]

Ibn

Sīnā

“If the mercury be pure, and if it be commingled with and solidified by

the virtue of white sulphur which neither induces combustion nor is

impure, but on the contrary is more excellent than that prepared by the

adepts, then the product is silver. If the sulphur besides being pure is

even better than that just described, and whiter, and if in addition it

possesses a tinctorial, fiery, subtle and non-combustive virtue, in

short if it is superior to that which the adepts can prepare, it will

solidify the mercury into gold.”

[95]

Ikhwān al- Ṣafa

If mercury was pure and if sulphur was free from impurities and if their

parts are comingled, and if their quantities were at the appropriate

ratio …then ibrīz gold will be formed

after a very lengthy period of time.[96]

Summa

“Therefore, 'tis now clear from the precedent, that if clean, fixed,

red, and clear sulphur fall upon the pure substance of argentvive (being

it self not excelling, but of small quantity, and excelled) of it is

created pure gold.”[97]

To conclude, it is clear that the constitution of metals according to

the sulphur-mercury theory is the same in the Summa as it is in

Arabic alchemy, from which it was derived.

e-

The Theory of the Three Principles:

Mercury,

One of Berthelot’s main hypotheses was that the theory of the three

natural principles was not mentioned in the Arabic works. Newman stated

similar views. This theory and the inclusion of arsenic as the third

principle was Newman’s second main argument to establish the

TP as the source of the

Summa: “Let us now point out

that the inclusion of arsenic among the metallic principles is not

easily extracted from the Arabic sources that our texts may have used”.

He then concludes that “The Summa

and the TP share the unusual

theory that arsenic must be included among the metallic principles: this

further substantiates our view that dependence – let us now say a direct

dependence – exists between the two texts.”[98]

Nevertheless, the three principles – mercury, sulphur and arsenic – are

always grouped together in Arabic alchemical texts whenever spirits are

discussed. This naturally also applies to Jābir.[99]

Arsenic was a major spirit, like sulphur, and there is extensive

literature on its preparation and use in chemical operations.[100]

Thus, the conclusions of Berthelot and Newman must have been based on a

lack of familiarity with Arabic sources and a very limited number of

available Latin texts translated from Arabic. None knew Arabic;

Berthelot relied on few texts of Jābir of the allegorical category

translated for him, and Newman relied on a very small number of

available Latin translations.

Jābir

“And one of its principles is arsenic which has preparation, work and

precious tincture; this is in addition to the high quality of this

principle and its nobility”.[101]

“We have to believe also that sulphur is one of the spirits and it is

necessary for the gold work; and arsenic is one of them and it is

necessary for the silver work; and if arsenic is used in the gold work

it will be deficient, and if sulphur is used in the silver work it will

be deficient.”[102]

Summa

“It now remains that we at present speak of arsenick. We say it is of a

subtile matter, and like to sulphur; therefore it needs not be otherwise

defined than sulphur. But it is diversified from sulphur in this, viz.

because it is easily a tincture of whiteness, but of redness most

difficultly: and sulphur, of whiteness most difficultly: but of redness

easily.”[103]

f- The Three Orders of Medicines

In the Book

of Seventy of

Jābir,

the concept of the three orders of medicines

is

mentioned in numerous chapters. The Summa contains

complete texts describing

this concept that correspond to the texts of the Book of Seventy

[104].

Further, numerous chapters in the Summa are based on this concept

also.[105]

We have discussed this topic elsewhere.[106]

UNIQUE JĀBIR TRAITS IN

THE SUMMA

Besides the discussions given above of Berthelot’s assumptions, we would

like to close Part I of this essay by showing three unique traits of

Jābir’s writing, which distinguish his Arabic works. These same

distinguishing features will be found again in the

Summa and the other Geber

Latin works.

a-

“Our Volumes”

Jābir wrote scores of books and treatises, for which he compiled three

fihrists (indices). These are listed in the

Fihrist of Ibn al-Nadīm. More

recently, Paul Kraus devoted one full volume to catalogue the works of

Jābir.[107]

Within these contexts, it is not surprising to find Jābir continually

referring to his numerous other volumes or books. This referral became a

characteristic feature of his style.[108]

In each of the four Latin tracts, Geber also speaks of his “other

volumes”.[109]

He declares that the Summa is the sum of what he had written in

his “other volumes”.[110]

Certainly, those “other volumes” cannot possibly be the minor texts

traditionally linked to the Summa.

As we shall see below, Julius Ruska, followed by William R. Newman,

assumed that the Riccardiana DIP

was a source for the Summa.

Ruska based his assumption on a single paragraph in the DIP which

refers to the author’s other volumes.[111]

We conclude from all this that the expression “our volumes” does not

apply to any of the above few Latin works. The expression “our volumes”,

repeated in each of the Geber works, points out to an author who had

written a large number of works on alchemy. Such an author cannot

possibly be a pseudo-Geber, as we do not know of any 13th

century Latin author who wrote so extensively on alchemy. Nor do we know

of any Arabic or of any pre-Arabic author. The only known author who had

composed scores of treatises and books on alchemy was Jābir, and his

style is reflected also in the Latin works.

b-

The Principle of the Dispersion of Science

Paul Kraus affirms that one of the most characteristic traits in Jābir’s

works is his continual declaration of not having exposed the full truth

in one place only, but that he had distributed the alchemical knowledge

throughout his countless treatises.[112]

He constantly advises the student of the Art to collect and study his

books. The Latin works of Geber also exhibit this same trait.

Jābir

“Understand that we have compiled in this art many books in numerous

topics and arranged them in different ways. Some were related to others

and some were complete in themselves […]. Each complete book is adequate

on its own. As to those books that are related, each one needs the

other, and no person can benefit by using them unless he gets hold of a

complete collection (and) read them all and learn their purposes.”[113]

Geber

“We declare that we have not treated of our science with a

continued series of discourse, but have dispersed it in diverse

chapters. And this was done; because, if it had been delivered in

a continued series of speech, the just man, as well

as him that is evil, might have usurped it unworthily. Therefore we have

concealed it in places, where we more openly speak; yet not under an

enigma, but in a plain discourse to the Artist.”[114]

c-

Jābir’s Books of ‘Sums’

It is not rare to find similar declarations in Jābir’s Arabic works, and

in the Summa. The opening paragraph of the

Summa is similar to the

corresponding one in his “Book of Seventy.” Jābir distinguished

between his larger and smaller books and in the preface to the former,

sometimes he states that a larger book is a sum of the knowledge

dispersed in the smaller ones.

Jābir

“Since there appeared many books of ours on this Art that is called

ḥikma (philosophy) which has no limit and is the ultimate of

philosophy, it became unavoidable that we should put down a book that

explains our previous abbreviated words; so we are explaining one word

of a certain art <in the previous abbreviated treatises> by a hundred

words of the same art <in this volume>. So that this volume <Book of

Seventy> contains what was in our former and our later books.”[115]

“We have written before this book of ours several books dealing with

such fundamentals like these, and all are dispersed. We have made this

book of ours like the sum of those fundamentals, and arranged it

in twenty parts.”[116]

Summa

“Our whole Science of chymistry, which, with a divers compilation, out

of the books of the ancients, we have abbreviated in our volumes, we

here reduce into one Sum. And what in other books written by us

is diminished, that we have sufficiently made up, in the writing of this

book of ours, and supplied the defect of them very briefly. And what was

absconded by us in one part, which we have made manifest in the same

part, in this our volume; that the compleatment of so excellent and

noble a part of philosophy, may be apparent to the wise.”

[117]

II

JULIUS RUSKA’S HYPOTHESIS

ABOUT THE RICCARDIANA

LIBER

Ruska’s and Newman’s Assumptions

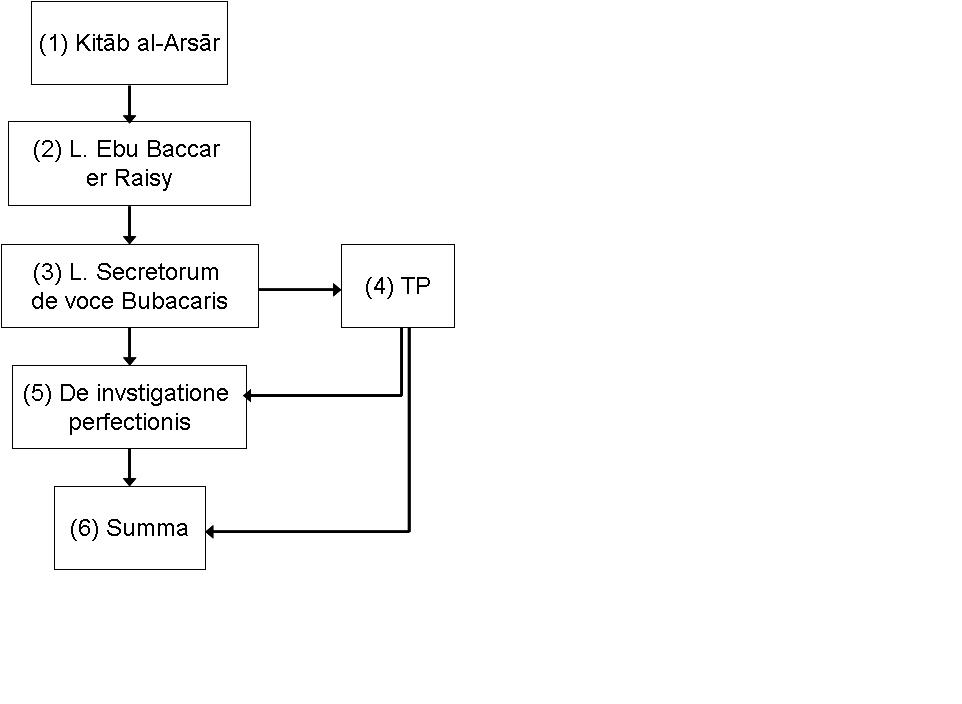

The following chart is a reworked copy of the one that was published by

William Newman to summarize his assumptions regarding a pseudo author of

the Summa perfectionis.[118]

We shall use it here also to summarize the assumptions of both Ruska and

Newman.

In 1925, Ernst Darmstaedter discovered a

codex in the Riccardiana Library of

In that period, Julius Ruska was deeply involved in his study of al-

Rāzī, and in 1935 he wrote an extensive paper in which he assumed that

this newly discovered DIP (number 5) is a reworking of

Liber Secretorum Bubacaris of

the B.N. of Paris[120]

(number 3). He declared that the attribution of the DIP to Geber

was erroneous – “only one example of the thoughtlessness with which

ignorant writers and scribes put arbitrary names to alchemical

treatises”[121]

- and he decided to include it in his study of the Latin works of al-

Rāzī.[122]

Ruska even suggested further that the last part of the DIP had

been even written by a late Latin author (which comes under number 4)

who would have also been the author of the

Summa[123]

(number 6). He considered

that Liber Secretorum Bubacaris

(number 3) was a reworking of

Liber Ebu Baccar er Raisy of Palermo (number 2), which was a

translation of Kitāb

al-asrār

of al- Rāzī (number 1).

In 1986, William R. Newman adopted all of Ruska’s assumptions and based

his work on them, and his main goal was to search for the unidentified

Latin author that was imagined by Ruska. For this purpose, he conceived

a maze of bewildering assumptions with abundance of Latin citations to

conclude that a previously unknown Paul of Taranto, a compiler of a

treatise with the title of Theorica and practica (number 4), was the

author of both, the Riccardiana

DIP (number 5) and the Summa[124]

(number 6).

We shall prove in this part of our thesis that all the assumptions of

Ruska and Newman are untenable and are without foundation. And since the

Riccardiana DIP is pivotal in Ruska’s and Newman’s assumptions,

the analysis and discussion of this treatise will be a major component

in this paper To do

this we shall discuss all their assumptions as illustrated in the

diagram, under the following main headings:

·

The Latin MSS of

Kitāb al-Asrār

of al- Rāzī:

We shall prove here that the

·

Ruska’s Assumption that the Riccardiana

DIP

is an Edition of Liber

Secretorum De Voce Bubacaris

: We shall prove here that the DIP (no. 5) is not an edition of

the Bubacaris (no. 3).

·

Attribution to a Latin Author:

We discuss here why Ruska’s assumption of the attribution of part of the

DIP and of the Summa to a Latin author (no. 4) is

unsubstantiated.

·

The Jābirian Paragraph of the

DIP

on which Ruska and Newman Based their Hypothesis of a Latin Author of

the

Summa:

We prove here that the single paragraph on which Ruska had based his

conjecture about a Latin author is simply a translation of one of

Jabir’s recognizable statements. This fact alone disproves the whole

hypothesis of Ruska and Newman about the imaginary Latin author (no. 4).

·

Arabic and Islamic Expressions in the

DIP:

We go a step further here to prove that the DIP as a whole is

rich in Arabic and Islamic religious and non-religious expressions,

including the part which Ruska had assumed to be written by a Latin

author.

·

Arabic Technical Terms in the

DIP:

We continue our proof that the DIP, including the part which

Ruska had assumed to be written by a Latin author, is rich in Arabic

technical terms which are not part of the usual terms that a Latin

author will use in his writing.

·

Jābir as the Likely Main Author of the DIP:

We prove here

that the major part of the DIP

was written by

Jābir, contrary to Ruska’s

assumptions. Our proofs are supported by the fact that the DIP

refers to Jabir’s

Libro quietis

(Kitāb al- rāḥa), and

we discuss this book in some detail.

·

Further Examples from Newman’s Assumptions:

After we have proved that the whole structure shown in the following

diagram is imaginary, we give few further examples

from Newman’s assumptions to

demonstrate how they are without any foundation.

·

The TP as a Compilation:

we end our paper by giving some further examples to illustrate that thTP

of Paul of Taranto is a mere compilation from translations of Arabic

alchemy. This excludes any possibility for it to be a source for the

DIP or the Summa as was assumed by Newman, (numbers 4, 5 and

6 in the diagram).

This list of topics should guide the reader in selecting what topic is

of interest to him. If reading the whole paper is not possible we advice

the reader to read: “The

Jābirian Paragraph of the

DIP

on which Ruska and Newman based their Hypothesis of a Latin Author of

the

Summa.”

This is a short text, but is of great significance.

Fig. 1 –

The assumptions of Ruska and Newman

Ruska assumed that an unknown Latin author (4) wrote part of the DIP (5) and that he wrote also the Summa (6). Newman based all his work on Ruska’s assumptions and he imagined that the unknown Latin pseudo author is called Paul of Taranto (4) who wrote a treatise TP (4), the DIP (5) and the Summa(6).

The Latin MSS of

Kitāb al-Asrār

of al- Rāzī

It is known, that

Kitāb

al-

asrār

(Book of Secrets) of al-

Rāzī

[125]

is a practical treatise on alchemy, devoid of theory. In the first two

parts, it gives a classification of substances and a description of

alchemical apparatus, and in the third and largest part, practical

recipes. This work remained little known in the West throughout the

centuries and the number of available Latin MSS is small.[126]

Ruska examined six of them: 1) BN 6514; BN 7156, both from the 13th

century; 2) Oxford Bodleian Digby 119, 14th century; 3)

As the “books of secrets” on various subjects were very common, and in

order to distinguish one from the other, the name of an author was

customarily attached to the title. In this way, the first four copies,

listed above, carried the name of “Bubacar”, while the latter two –

Sloane and

The importance of KA lies in

its first two parts, on substances and apparatus, which in fact

constitute a very small fraction of the whole work; and they were

frequently quoted by compilers. On the other hand, the third part, on

recipes, although it constitutes the major part, seems not to have been

cited in its entirety, probably because a vast number of recipes, from

both Arabic and Latin sources, were available to compilers[129]

This is the reason why the Latin versions of

KA differ in the content and

arrangement of the third part.

The four “Bubacaris” MSS have complete Latin translations of the

first two parts. In 1927, Stapleton et al. published an English

translation of the first two parts of

KA, together with extracts

from the third.[130]

An important feature of this translation is that it used both an Arabic

MS and a Bubacaris MS (B.N.

6514), finding small differences between both.

In 1935, Ruska published a study on the Latin translations and

re-workings of KA, and two year later, a German translation

including all three parts.[131]

However he mistook KA that he

had translated for a different work of al-Rāzī, which is

Kitāb sirr al-asrār (The Book

of the Secrets of Secrets).[132]

While he described briefly the Bubacar MSS in his 1935 study, he gave

excerpts from the Sloane and Palermo MSS.[133]

The translation of the Sloane MS was made by a Syrian priest in

Moreover, the six Latin

MSS reported by Ruska can be differentiated into three types. The four

Bubacaris manuscripts correspond to one type, while the Sloane

and Palermo MSS are second and third types. The differences among all

three types are noteworthy, thus the possibility of any one being a

reworking of another seems remote.

We draw attention here also to a discrepancy in the historical dates of

the six MSS. We do not know for sure which MSS preceded the other. If we

consider the dates reported in Ruska’s paper, we notice that the

Ruska’s Assumption that The Riccardiana

DIP is an Edition of

Liber Secretorum De Voce

Bubacaris

The DIP is an extensive

treatise.[136]

Written on 24 folios, comprising a total of 45,200 words, it is compiled

from different sources. However, besides the initial few pages dealing

with substances and equipment,[137]

Ruska could not find any Rāzian Latin texts matching the DIP.

Moreover, his analysis showed that the share of Rāzian Latin texts

amounted only to about 13% of the full MS.[138]

For this reason, he had to resort to the Arabic

KA.

However, if Ruska wanted to prove that the

DIP was a new edition of the

Bubacaris, the Arabic text of

the KA was not the right

place to look for. And, if he was searching for the real sources of the

DIP, he should not have

limited himself to the Arabic

KA, but he should have

surveyed the numerous extant works on Arabic alchemy, particularly

Jābir’s, since after all, the DIP

does carry his Latin name.

But, since Ruska limited himself to

KA, he had no other options

but to compromise. Thus, sometimes he writes that the DIP text

corresponds on the whole (im

ganzen) to KA , while at other times he says that it is a

rough approximation (annähernd).[139]

If he would have adhered to proper comparison rules, the share of

materials taken from KA would

diminish considerably. To illustrate: upon finding a difficulty in

comparing the Arabic KA with

the DIP, he explains: “The

‘DIP’ text corresponds

on the whole (im ganzen)

to the first prescript in KA’s chapter on the ‘egg’, however at

the end it has a strong infringement or intrusion. The end seems to have

been taken from a third source”[140]

Toiling in this way, to find in the Arabic

KA similarities to the

DIP, Ruska was able to add a

further 27% to the share of Rāzian sources in the

DIP, raising the total to

about 40%. But the remaining 60% still had to be attributed.

Attribution to a Latin Author

As mentioned above, Ruska could not find in the Latin

Bubacaris

and the Arabic

KA

similarities justifying the hypothesis that the

DIP

was a reworking of the Latin

Liber Secretorum Bubacaris.[141]

Thus, he had to admit that the compiler had have recourse to other

sources. And he ventured to attribute the last part of the

DIP

to a Latin pseudo-author.

To substantiate his hypothesis, Ruska focused on the

DIP

section dealing with alums and salts (fols. 21r to 24r), which

corresponds to the last paragraphs of Part IX and the full Part X, to

conclude:

“What distinguishes these pieces from the largest part of the preceding

compilations is obviously only due to their mature late Latin

formulation. Here we do not have to deal with translations of Arabic

writings, but with original Latin texts, which follow content-wise older

models of the translation literature. In their style, however, they are

quite Latin and do not reveal the spirit of the Arabic language.”[142]

However, in the first place, here Ruska made an assumption without

presenting any evidence. Moreover, the description of the style of the

text as “mature late Latin” is inaccurate. The text under analysis was

transcribed in the last decades of the 13th century but the

translation and compilation of the

DIP

were made obviously before transcribing the Riccardiana MS. We still

have to keep in mind the state of the knowledge on alchemy in the Latin

West by the middle of the 13th century, as portrayed by Roger

Bacon.[143]

The Latin literary style as a criterion to decide on the origin of this

part of the

DIP

is not justifiable. It must be reminded that a translation may be

literal or edited. In the latter case, a translator has his own

understanding of a text, to then write it in another style. Thus, e.g.

the translators of

Finally, another genre is compilations, taken from several sources, as

is the case of the

DIP.

Compilers may perform some editing. The work may carry the name of the

compiler, and when it includes material from an important author it may

bear his name. In the latter case, we have examples from both Arabic and

Latin texts.

Kitāb Ṣundūq al-ḥikma

(Chest of Wisdom) is a compilation of chemical and alchemical recipes,[145]

and it is ascribed to

Jābir. The

Liber claritatis

which

is a compilation of

chemical recipes translated from Arabic is ascribed to Geber, in the

same way as the DIP

which is ascribed to Geber also[146].

Another example is the

Artis Chemicae Principes

or

De anima in arte alchemia

which is a compilation of Arabic chemical and alchemical recipes

attributed to Avicenna (Ibn

Sīnā).[147]

These three Latin compilations of Arabic alchemy and chemistry

(including the

DIP)

appeared in the thirteenth century at about the same period.

As a matter of fact, Ruska had based his hypothesis of a Latin author on

a single paragraph in the

DIP,

which

is a

Jābirian

one as will be now shown.

The Jābirian Paragraph

of the

DIP

on which Ruska and Newman Based their Hypothesis of a Latin Author of

the

Summa

Ruska had based his hypothesis of a Latin author for part of the

DIP and further, that this

same author would have written the

Summa on the following

paragraph:[148]

“

De quorum nominibus, naturis et operationibus hic dispersa in diversis

voluminibus posuimus capitula, et induimus opiniones diversas.

Alibi tamen cum Deo

summam omnium, quae sparsim

tradidimus, aggregabimus cum veritate probationis in summa una sermone

brevi, in qua quidquid nostra volumina utile seu superfluum continent

aut diminutum, hic per illam ibique per haec sanae mentis et diligentis

indagationis artifex absque errore reperiet et perveniet ad desideratum

perfectae artis actum et expectatum laboris effectum.

Et nos non collegimus Iob aliud multa ex

antiquorum dictis et in voluminibus nostris ea multiplicavimus, nisi ut

ex illis eliceremus secretum eorum, et vitaremus errores, et ex eorum

coniecturis nostri roboraremus perscrutationem sermonis via brevi et

veritate perfecta, ad quam faciente glorioso et sublimi Deo, licet cum

longi vigilia studii et magni laboris instantia usque quaquam pervenimus,

et earn totam in libro qui Summa intitulabitur, non sub illorum

scribemus aenigmate vel figuris, neque ita lucido trademus sermone, quin

illum accidat necessario insipientes latere eosque subire errorem. Sed

traditionum omnium assumentes arcanum ex his, quae perquisivimus,

vidimus atque palpavimus. et certificati sumus cum experientia vera,

tali sermone volente Deo explicabimus. Quod si se ad ea bonae mentis

artifex exercitaverit, se totum [aut saltem partem] artis excelsae

fructum Dei dono adinvenisse laetabitur.”

In

this paragraph the author makes three important declarations:

1-

He refers to his “various volumes” (diversis

voluminibus).

2-

He has dispersed alchemical knowledge in these volumes.

3-

Therefore he will write a “sum book” (summa).

This is a Jabir’s paragraph and we have already cited similar ones at

the end of Part I under “Jābir’s Books of Sums” when we discussed

the ‘Unique Jābir Traits”.

We have shown that Jābir was the only author who had written numerous

volumes throughout which he had dispersed knowledge and who wrote “sums”

of this scattered knowledge.

Also in this same paragraph, the author employs four Islamic expressions

of praise to God: “cum Deo”, “glorioso et sublimi Deo”, “volente Deo”

and “Dei dono”.[149]

As it was discussed above also, Geber’s works included this kind of

Islamic expressions. Moreover, Geber was acknowledged among the Latin

alchemists up to the 17th century as the author that most

characteristically praised God, this being a sign of the Arabic origin

of these works.[150]

This paragraph is therefore, a translation from an Arabic Jābirian

text. It ought to be very alarming for historians of science to realize

that the whole hypothesis of Julius Ruska is based on his false

interpretation of this single clause; and that the whole intricate

structure of William R. Newman and his voluminous work concerning a

pseudo Paul of Taranto and his imagined role in the history of Latin

alchemy, is built on Julius Ruska’s false understanding of just one

Jābirian paragraph.

Arabic and Islamic Expressions in the

DIP

The DIP as a whole, including the section selected by Ruska as a

Latin original text, is rich in Arabic and Islamic expressions. The

assumption that they were insertions by the author in order to imitate

the Arabic style needs sound substantiation.

It seems infinitely more probable that, inversely, they are an

intrinsic part of the fabric of the DIP.

Latin translators used to purge the Arabic texts from conspicuously

Muslim expressions, like the name of the Prophet and other explicit

Islamic religious idioms.[151]

However, there are some Islamic expressions that can be applied to any

religious belief, especially those that praise or glorify God. These

expressions were sometimes kept in the translations.[152]

Among the many Islamic expressions, one sentence reads: “Benedictus

igitur sit gloriosus et sublimis Deus qui nihil fecit regimine carens”,

meaning “Therefore be blessed the glorious and sublime God, who made

nothing which lacks order”.[153]

This sentence is similar to one or two verses in the

Qu’rān.[154]

The DIP includes also 56

short Islamic religious expressions, such as “cum deo”, “cum deo

volente”, and the like, distributed throughout its 24 folios – 10 of

which appearing in the section selected by Ruska as being written by a

Latin author.[155]

In the Arabic alchemical literature, these kinds of expressions tend to

occur at the end of recipes and they are translations of the Arabic “inshā’allāh”

(if God wills) and its other Arabic forms. The frequency of their use

varied from one author to the other, but they are occurring in all of

them. This is a typical Muslim phrase, derived from the

Qu’rān. Its use is mandatory

and is deeply rooted in Islamic culture.

[156]

The non-religious expression “scias hoc” appears 31 times – 12 of them

in the section selected by Ruska. It means “know this”, “understand

this” and it is typical in Arabic texts whenever the author wanted to

stress the importance of an idea or a prescription.[157]

The phrase “et est de secretis” occurs several times in the

DIP, also being a typical

expression in Arabic alchemy.[158]

A quantitative analysis also serves to underscore the difference between

Jābir’s and al- Rāzī’s texts. In the latter’s Arabic printed edition of

KA,[159]

the expression “if God wills” occurs 4 times only, while “know this”

occurs 7 times throughout all its 116 pages. This is in overt contrast

to Jābir’s Arabic texts. In his

al-malāghim books – devoted to the practical alchemy of amalgams-,[160]

between folios 2a and 36a there are 48 expressions of “if God wills” and

17 of “know this”.

God references by Latin authors

We have surveyed several alchemical treatises written by Latin authors

and other works translated from Arabic from the 12th century

on, looking for the word “God” and others signifying “God”, together

with their qualifications.[161]

We found that the qualities attributed to God by Muslim alchemists were

not used by Latin writers. That is to say, it is possible to distinguish

a Latin from an Islamic author through the occurrences of the word

“God”.

Latin authors had a particularly Christian style to refer to God. For

instance, Arnald of Villanova, in

Chymicall Treatise, mentions the word “God” devoid of the Islamic

attributes. In this work, the term “Holy Ghost” appears more times than

“God” while the latter is defined “I say that the Father, Son and Holy

Ghost are one, yet three”.[162]

And still, “The Word was a Spirit, and that Word the Spirit was with

God, that is with himselfe, and God was that word, he himself was the

Spirit”, based on John 1:1. Thus, in this treatise we find a clear

Christian tone, completely different from the Islamic.

In the Book of Quintessence,

by John of Rupescissa (d. 1365), the author begins his essay “in the

name of the Holy Trinity”, in opposition to the Qu’ranic verse which

opens an Arabic work like the

Liber de Compositione Alchimiae. God is designated several times as

“our Lord God”; the name “Jesus Christ” is used, and in no instance

references to God include the Islamic attributes.[163]

To quote one more example, in New

Pearl of Great Price, written by Peter Bonus in the 14th

century and edited by Janus Lacinius in the 16th, we find

once again the same Christian style of references to God (without the

Islamic attributes), besides the expressions: “Christ”, “Jesus Christ,

the Son of God”, “our Saviour Jesus Christ” and “our Lord Jesus Christ”.[164]

Arabic Technical Terms in the

DIP

Many technical terms clearly betray the Arabic origin of the

DIP. One instance is the

units of weight. Latin translations of Arabic alchemical works generally

used the “libra”, a translation of the Arabic word

raṭl.

One raṭl

was usually equivalent to about 468 grams, although this value had

regional variations.[165]

The Roman libra or pound was used throughout

Arabic texts also use the dirham,

which is equivalent to about 3.6 grams.[170]

In the DIP, the

dirham is translated as

drachma, and occurs 54 times.[171]

In

“Ocab” corresponds to the Arabic

‘uqāb, meaning eagle. This word is

much used in Arabic alchemical works as a pseudonym of

nushādir (sal-ammoniac). The

word “ocab” appears 101 times in the

DIP,[173]

while in other Latin translations or works written by Latin authors, the

term employed was sal ammoniacum.

Like this, there are many other terms in the

DIP that kept closeness to

their Arabic origin. A few examples are presented in Appendix 3.

Jābir

as the Main Author of the DIP

If we accept

Ruska’s assumption that the Rāzīan contribution to the DIP

amounts to 40 percent of the whole treatise, we are left with 60 percent

that should be accounted for. We have demonstrated that the pivotal

paragraph which Ruska imagined was written by a Latin author is a

translation from Jābir and that the whole section which Ruska tried to

assign to a Latin author is an Arabic translated text. Therefore we are

left with one choice only which means that Jābir is the main author of

the DIP. Let us elaborate.

The dominant figure in Arabic alchemy was Jābir ibn Ḥayyān. Many

alchemical works bear his name, as it was pointed out above. On the

other hand, al- Rāzī wrote a much smaller number of treatises, the most

renowned of which is KA.[174]

For Arabic writers on alchemy, Jābir was the main authority. They quoted

him systematically more often than al- Rāzī. For example, al- Jildakī’s

Nihāyat al- ṭalab – a

commentary to al-‘Irāqi’s treatise on the cultivation of gold –[175]

mentions ten times one work only by al- Rāzī, whereas Jābir is mentioned

194 times and 42 works are cited.[176]

This same huge disparity is found in the literature of Arabic alchemy

and it is not difficult to explain. Al- Rāzī had an interest in alchemy

in his youth, for a period of about ten years, to later devote himself

to medicine. On the other hand, Jābir devoted his long life – 90 years,

according to al-Jildakī - mainly to alchemy.

We like to mention here that Jābir was the main source for al- Rāzī.

This was demonstrated in detail by Stapleton.

[177]

Earlier, Abū Maslama al- Majrīṭī (d. 1008) had shown in his book

Rutbat al- ḥakīm that al- Rāzī did not discuss any topic

that was not discussed earlier by his ‘teacher‘ Jābir,[178]

and that Jābir had revealed facts that remained obscure to his ‘student’

al- Rāzī.[179]

Another noted alchemist, al-Ṭughrā’ī (d. 1121) claimed in his book

Mafātīḥ al-raḥma, that most of al- Rāzī’s twelve books were copied.[180]

In recent times, Ruska acknowledged that the twelve books of al- Rāzī

are influenced by the teachings of Jābir.[181]

Thus, it cannot surprise us that a vast disparity is reflected in the

alchemical works that were translated into Latin. The translators had a

much larger choice from Jābir’s works on both practical and mystical

alchemy than from al- Rāzī’s works. This helps to explain the existence

of several Geber Latin works.

Therefore, the compiler of the Riccardiana

DIP would have had two main

Arabic sources: the lesser would be al- Rāzī, and the main one, Jābir.

Libro quietis (Kitāb al- rāḥa)

A further argument for Jābir is found in a paragraph in fol. 6r of the

DIP: “Diximus

superius in libro quietis

utilia et non utilia, ubi diximus congelationes spirituum et

coniunctiones corporum, et subtiliter diximus in operatione supradicti

libri”.

Here the author states that he had talked above, in the “libro

quietis” (Kitāb al-rāḥa),

of the congelation of spirits, the union of bodies and their

preparations.[182]

Ruska had noticed this paragraph, but he was not able to find any

mention to the libro quietis

or the Kitāb al- rāḥa,

neither in Bubacaris, nor in

KA. Thus, he concluded that it must have referred to a different

unknown source.[183]

However, as al- Rāzī’s Kitāb al-

rāḥa is not a book on alchemy,[184]

the libro quietis mentioned

in the DIP must be

Kitāb al- rāḥa of Jābir. This

work by Jābir is missing, but we have significant information about it

from al- Ṭughrā’ī and al-

Jildakī.[185]

The importance of Kitāb

al- rāḥa may be appraised from the following statement in al-

Jildakī’s Nihāyat al-

ṭalab:

“And since to us was revealed everything concerned with this science we

devoted this our book and K.

ghāyat al-surūr and K.

al-shams al munīr and K. al-taqrīb

fī asrār al-tarkīb

and K. sharḥ k. al- rāḥa of

Jābir (Explanation of the Book of Rest) to important, useful and

comprehensive practical discourses, which if mastered by the seeker of

knowledge would enable him to grasp all the principles and doctrines of

the Art.”[186]

From the paragraph in the DIP,

we learn that the libro quietis discusses the “coniunctiones

corporum”, that is, the union of bodies or their alloying. From al-

Ṭughrā’ī , we learn that Kitāb

al- rāḥa deals with the union (tazwij’)

of bodies. The word “tazwij”

literally means intimate union and, in an alchemical sense, mixing or

alloying. In other words, “tazwij”

and “coniunctiones” convey

similar meanings. Al- Ṭughrā’ī would also quote extensively from Bālīnās

and Jābir. An instance of a long quotation taken from

Kitāb

al- rāḥa is the following:

“And Bālīnās was speaking in this chapter about the method of mixing and

the union of the thin (rarefied) with the dense (thick). And his

meanings are similar to what Jābir had said in

Kitāb al- rāḥa, although the

approaches are different; but the scientist perceives with God’s light

and understands the relative relationship. Jābir ibn Ḥayyān said that no

whiteness can take place, or redness, without the spirits and the

spirits of bodies. And there is no way of differentiating and of

bringing out the gentle spirit of the body except by the spirits of the

spirits, This is because the spirits of bodies yearn for the spirits of

spirits and seek them since all of them are spiritual and aeriform.

Therefore if they are subjected to the heat of fire they fly and

evaporate. So if the spirits are mixed with the spirits of bodies they

cling to each other by an adherence that cannot separate.”[187]

At the end of this long citation, Al- Ṭughrā’ī comments, “If Jābir in

his book, which nobody has surpassed us in compiling, had given only

this chapter it would have been sufficient, because it contains most of

the principles that are needed in this Art.”[188]

Recapitulation – the Bringing to an End of Ruska’s and Newman’s

Assumptions

We have discussed until now in detail why the DIP cannot be

considered as a re-working of the Bubacaris, why it was entirely

compiled from sources of Arabic alchemy, mainly from Jābir, why the

pivotal paragraph on which Ruska had based his hypothesis is translated

from Jābir, and why no part of the DIP was written by a Latin

author.

Having refuted Ruska’s

speculations and since Newman had built his work on Ruska’s hypothesis

(see the diagram), it follows that all Newman’s assumptions are without

foundation.

With this conclusion, it is irrelevant to discuss the arguments given by

Newman on the interdependence of the Bubacaris, the TP,

the DIP and the Summa. There is no need for this anymore.

Nevertheless, we shall give few examples.

Further Examples from Newman’s Assumptions

We have given till now ample evidence about the Arabic identity of the

Summa and the DIP and we have shown that the corpuscular

theory and the mercury alone theory are of Arabic origin and were not

the invention of the pseudo Paul of Taranto. We have shown also at the

end of Part I that all alchemical theories in the Latin language came

with the translation of Arabic works in the twelfth and thirteenth

century. Nevertheless we

shall give now further samples of the kind of assumptions that Newman

had used in his work.

The Bubacaris and the Summa

Newman would suggest that the

Bubacaris was a source for the

Summa.[189]

He had studied the two Latin translations of Arabic works available to

him – Geber’s L. Misericordiae

and De Re Tecta by

pseudo-Avicenna – and since he could not find in them anything

comparable to the Summa, he concluded that

it must have had the

Bubacaris as a source.[190]

This hypothesis would be a priori

unlikely as these are very different works: the

Bubacaris is a practical

treatise, including very little theory, while the

Summa is a theoretical work,

with a minor content of practical alchemy. Thus, any potential

similarities would be too fragile a ground to establish a dependence of

either of them on the other. However, it is worthy to review one of the

instances (about ceration) which Newman chose to base his assumption.

Ceration

This instance was deemed by Newman to be unique and would not occur in

any other alchemical texts except the Summa and the Bubacaris.[191]

It concerns the materials that ought to be used as agents of ceration.

He did not find such information in the two Arabic Latin translations

that were available to him.

According to Newman, Bubacaris is using sulphur and arsenic in

ceration, whereas the Summa is using mercury, sulphur and

arsenic. He says that the

author of the Summa has ‘divined’ the reason why the Bubacaris

had used sulphur and arsenic only, so he added mercury.

[192]

Newman thinks that ths alchemical knowledge is quite unique to the

Summa, but its ‘underpinning’ is found only in Bubacaris and

he concludes that the Summa had used Bubacaris as a source[193]

Summa

Putaverunt ideo aliqui cerationem debere ex oleis, liquidis, et aqueis

fieri: sed erroneum est illud a principiis huius magisterii semotum

penitus, et ex manifestis nature operibus reprobatum. Naturam enim non

videmus in ipsis corporibus metallicis humiditatem cito terminabilem ad

illorum fusionis et mollificationis necessitates posuisse.... In nullis

autem robus melius et

possibilius et propinquius hec humiditas cerativa invenitur qualm in

his-- videlicet sulphure et arsenico propinque-- propinquius autem in

argento vivo et melius.

[194]

The Smma here is advocating the use of spirits only (sulphur,

arsenic and mercury) for ceration and is opposing the use of oils,

liquids and waters[195].

Bubacaris

Inceratio corporum sapientissimi philosophi cum sulheribus(!) et

auripigmentis puris facere preceperunt quia commiscentur cum corporibus

si coniunguntur et si cum ipsis fuerint.

Elargant enim ea et diasol<v>unt et faciunt currere (pro currere cod.

legit cinerem). Et secundum quod multi dixerunt corpora incerantur cum

salibus aut boracis et non intellexerunt quod pertinet incerationi et de

salibus.

Non est tamen

inceratio nisi fuerit cum eis aut sulfur aut auripigmentum preparatum.[196]

Bubacaris

here is recommending using sulphur, arsenic, salts and boraces.[197]

This range of materials is not the same as the one in the Summa.

Jābir

Jābir discusses ceration in numerous books. We give here a selection

only:

-

Kitāb al-raḥma al-kabīr

(The Great Book of Mercy)[198]

and Kitāb

sharḥ Kitāb al- raḥma

(The Book of Explanation of the Book of Mercy)[199]:

Jābir advocates the use of mercury, sulphur, arsenic and sal-ammoniac.

- Kitāb

muṣaḥḥaḥat iflātūn (The Book of iflātūn’s Corrections)

[200]:

Mercury, sal-ammoniac and sharp waters.

-

Kitāb al- uṣūl

(Book of Principles)

[201]

Sal-ammoniac solution

-

Kitāb tadbīr al-arkān wa al-

uṣūl

(The Book of Treatment of Bases and Principles)

[202]:

Sal-ammoniac solution.

-

Kitāb al-tajrīd

(The Book of Abstraction)

[203]:

Sal-ammoniac solution.

-

Kitāb al-riyāḍ

(The Book of Gardens)

[204]:

Water of eggs’ white with sal-ammoniac, borax and tinkār; also the fat

of the horns of deer.

Comparing the Latin with the Arabic texts on ceration

Jābir’s materials for ceration are: spirits (mercury, sulphur and

arsenic), salts (mainly sal-ammoniac), borax, tinkār, sharp waters,

water of the white of eggs and fat or oil from the horns of deer. These

materials include all the reagents given in the Summa and the

Bubacaris,

Let

us

remember that ceration is a basic step in a series of operations of

Arabic alchemy, each one leading to the other, in order to obtain the

elixir for metals such as gold. It begins by calcination, followed by

ceration, solution and coagulation.

From the above comparison we conclude that the Summa and

Bubacaris are not dependent on each other and that their ultimate

sources are Arabic.

The

TP

and the

DIP

Newman had assumed that the DIP

had been based to some extent on the

TP of Paul of Taranto, since

some formulations are similar in both MSS. However, the fraction of such

similar formulations is very small relative to the full contents of the

DIP, representing a mere

3.3%.[205]

Thus, they cannot be taken as an argument for the dependence of the

DIP on the

TP, nor for Paul of Taranto

as the author of the DIP.

This similarity is due to one of two causes: either the

TP used the

DIP as one of its sources, or

both compilers used the same source. In addition to the very small

fraction of similarities, we noticed that the compiler of the

TP had cut down parts of some

formulations and removed the typical Arabic Islamic expressions. The

hypothesis that the Latin compiler of the

DIP had purposefully

introduced such Arabic and Islamic expressions is untenable.

Inter-dependence of the TP and the Summa

Under the title ‘The Theorica et Practica and its relationship to

the Summa’ Newman gave two main arguments to prove the

inter-dependence of the Summa and the TP. One was about

the composition of metals on the basis of the sulphur mercury theory,

and the second was in connection with arsenic as one of the principles.

These two assumptions were discussed above in Part I (see

‘The sulphur – mercury theory and the composition of metals’;

and also

‘‘The theory of the three principles: mercury, sulphur and arsenic”,

where we compared the Summa with the Arabic sources.

We proved there that this alchemical knowledge in both the

Summa and the TP is a basic one in Arabic alchemy. The

restriction of the search to a few Latin sources is the cause of this

flawed hypothesis.

Differences between the TP and the Summa

Newman went further, and in order to prove that the

Summa could not have been the

source of the TP, he paid

special attention to the differences between both texts. But in this

way, what he did prove, indeed, was their lack of similarity.[206]

The differences between the TP

and the Summa are

indisputable and there is no need to prove them. However, it is

inconsistent to infer from the differences that the

Summa is based on the

TP. On the other hand, our

discussion in Part I above clearly shows that all the chemical theories

in the Summa are based on

Jābirian alchemy.

THE

TP

AS A COMPILATION

Additional Examples

It is not our aim to give in this paper a thorough discussion of the

TP.

Its character as a compilation is stated in its colophon which

says that it was “compiled” by Paul of Taranto.[207]

The theoretical part of the TP

begins with a short article on “what things and what kind of things this

art takes as materials”. The text gives several cover names (decknamen)

for metals and their calxes. This reminds us of the tradition of Arabic

texts.[208]

Moreover, in one page only we can find several Arabic terms mentioned in

a distorted form such as, e.g. “sodebeb” (dhahab,

gold); “alkal” (al-kuḥl, stibnite);

“anec” (anūk, tin); “kasdir”

(qaṣdīr, tin); “sericon” (zarīqūn,

or sarīqūn, lead oxide); “usurub”

(usrub, lead); saffron of

iron is a translation of za’farān

al- ḥadīd.[209]

In the second article, dealing with the four principles (or spirits),

mercury has alternative distorted Arabic names, such as “azot”, “azet”

and “zambac”, from zi’baq. It

is also called “servus fugitivus”, which is the literal translation of

the Arabic pseudonym of mercury,

al-‘abd al-ābiq

(the fugitive slave). Among the names of sulphur we find the Arabic

kibrit. Arsenic is mentioned

by its Arabic name “zernech” from

zarnīkh.

Sal-ammoniac is called “almizedir” and “nischader”, from

nushādir, and “capocab” from

‘uqāb (eagle).[210]

The second part of the Practica,

contains practical procedures and recipes easily identifiable as taken

from translated Arabic works. We have examined the items and recipes

that fall between folios 39V and 45R.

[211]

There are 28 items from which 19 were identified by Newman to have

been‘re-written’ by the author of the TP from Latin translations

of Arabic sources.

[212]

These recipes are found in the original Arabic works also.

[213]

Sal Alkali

An article under the heading “how sal alkali should be made”, describes

how sal alkali, to make glass, is to be prepared from a herb. Newman

remarks that “this is the only recipe for sal alkali which I have found

in an alchemical text that describes the preliminary roasting necessary

for the production of potash. It probably reflects the author’s own