History of Science and Technology in Islam

The Arabic Origin of Summa perfectionis magisterii

And the Other Geber Latin Works

VI

The Translator of Liber fornacum

Additional Significant Information

Since my previous Brief Note on the Arabic Origin of Liber fornacum was published,[1] I came across additional information that confirms the fact that the Liber fornacum was without doubt translated from Arabic. We know now the name of the translator, the location where the translation took place and the date of the translation.

In 1922, Ernst Darmstaedter published his now classic German translation of Geber’s Latin works including the Testamentum.[2] In his edition he gave a list of the MSS that were known to him at the time of his publication. In June 1924 Darmstaedter published a short report ((Mitteilung) [3] in which he announced the existence of a manuscript at Bologna University in Italy containing the Summa, the Testamentum and the Liber fornacum.This is MS

Cod. Lat. 448 (756) of Bologna.

The exciting thing for Darmstaedter for which he devoted most of his Mitteilung is a note (Vermerk) written by the scribe. He edited carefully this note and it reads as follows:

“Explicit liber fornacum Jeberis translatus in Caliax (Cahax?) al(ias?) Vaheito(?), anno arabum (1) 720, per Rodogerum Hyspalensem (?).”

Darmstaedter professed here that according to this note the Liber fornacum was translated by Rodogerum Hyspalensem in Spain in the Arabic year 720 of Hijra which is equivalent to 1320 AD.

The use of the Arabic (Hijra) calendar is in itself significant. We have examples where Christian writers in Spain were using sometimes the Arabic calendar during the centuries when there was still Arabic rule in parts of Spain.

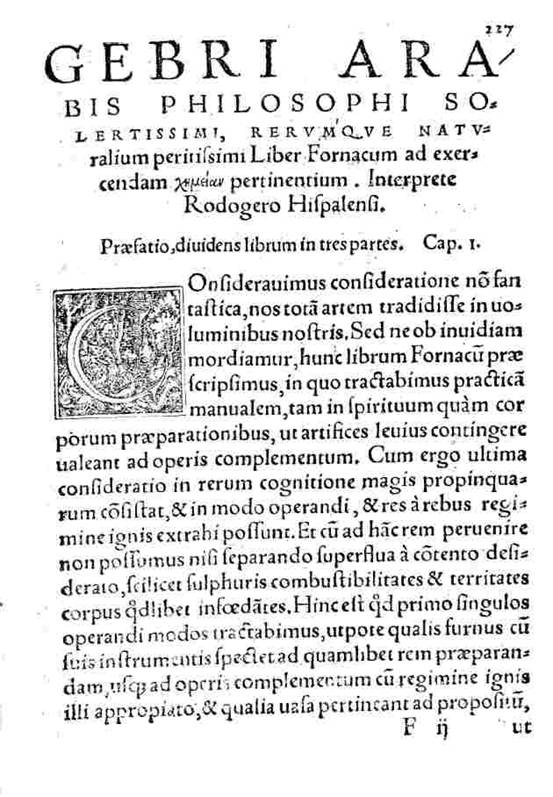

We must note here that Darmstaedter had translated the Latin works using the Nuremberg compendia of 1541 in which the name of the translator was given (Fig 1). But he edited that text by eliminating the name of the translator from his 1922 translation. Apparently, however, this was a bewildering discovery for him. In that period in the history of science the debate was acute between the advocates for a Latin-Pseudo-Geber and those who believed that the Latin works were translations from Arabic, Holmyard was a lone fighter against an enormous torrent of support for the Latin pseudo author. Renowned historians of chemistry like Von Lippmann and Ruska supported the Latin Pseudo-Geber theory and they used their immense authority to give it weight. Even within that prevailing atmosphere Darmstaedter he was obliged to declare that:

“Immerhin erscheint. es nicht unmöglich. daß der Liber Fornacum eine Übersetzung aus dem Arabischen ist, die in Spanien entstanden ist.“

which reads: “Nevertheless it appears that it is not unlikely that the Liber Fornacum is a translation from Arabic which was completed in Spain.”

Darmstaedter exposed further that two printed editions of the Latin works gave the name of the translator of the Liber fornacum and these were the Nürnberg edition of 1541 and of <Bern> 1545.

Darmstaedter says:

[Der Vermerk ist in jedem Falle von Bedeutung. auch deshalb. weil der Name der Rodogerus Hyspalensis als übersetzer auch in dem Drucke des Liber Fornacum, Nürnberg 1541 und <Bern> 1945 genannt wird. Der Titel lautet dort: „Gebri Arabis Philosophi Solertissimi ..Liber Fornacum. Interprete [4] Rodogero Hispalensi "]

This reads: [The note <at the end of the MS> is in any case of importance because the name of Rodogerus Hyspalensis as translator of the Liber fornacum appears also in the printed texts in the Nuernberg editions of 1541 and 45.[5] The title reads there: "Gebri Arabis Philosophi Solertissimi..Liber Fornacum. Interprete Rodogero Hispalensi"]

Darmstaedter then remarked that those publishers of the sixteenth century were not producing works of fantasy. They were publishing serious works and when they refer to translators in their published editions they rely on old and reliable sources.

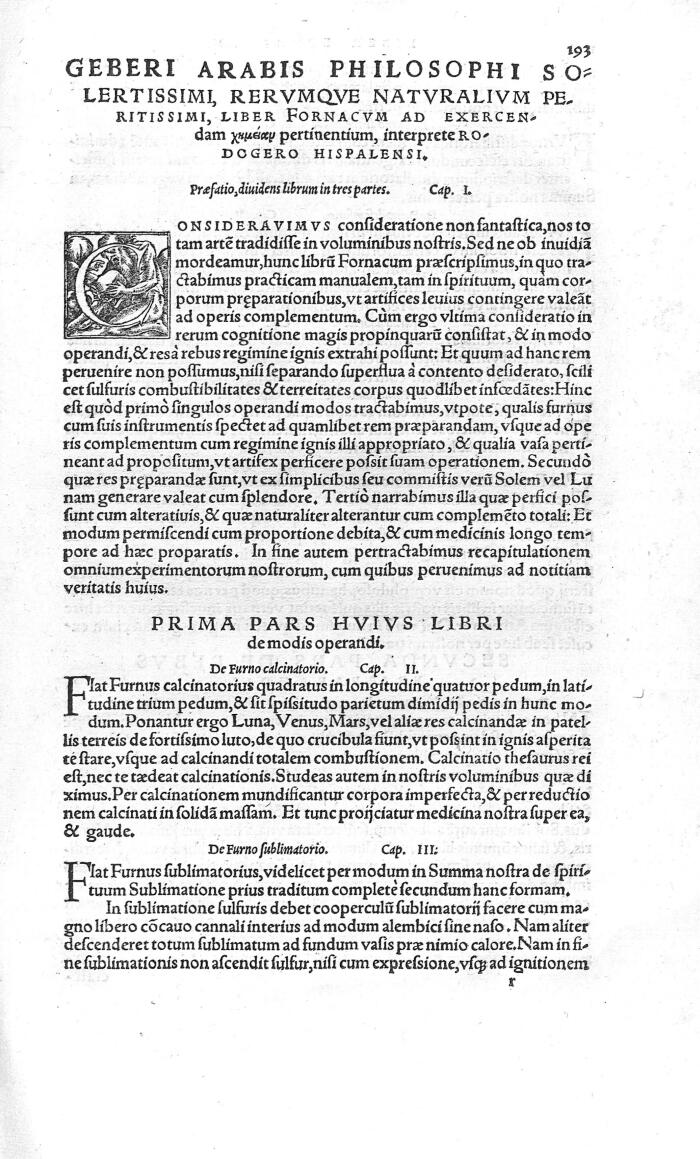

It is of importance to learn that prior to Darmstaedter, Hermann Kopp noticed in 1875 that the Basil printed edition of 1572 [6] gave the name of the translator of the Liber fornacum, namely Interprete Rodogero Hispalensi. . Kopp remarked that he could not know who that translator was.[7]

Both, Kopp’s information and Darmstaedter’s report or Mitteilung went unnoticed from the time when they were published in 1875 and 1924. No historian of science or chemistry ever since had referred to them. No one was willing to disturb the calm waters or to contest the established beliefs; on the contrary most historians of science were looking for further implausible assumptions to boost the fictitious theory of the Latin Pseudo-Geber.

To become conscious of the fact that there is at the present concrete evidence for an Arabic origin for Liber fornacum the historian of science needs to look thoughtfully now at the whole question of the Geber Problem.

Up to the present time the following MSS mention the name of the translator of Liber fornacum:

- Bologna University MS Cod. Lat. 448 (756), anno 1420

Geberi Arabis Summa perfectionis Magisterii cum Testamenta ac Libro Fornacum. translatus in Caliax (Cahax?) al(ias?) Vaheito(?), anno arabum (1)720, per Rodogerum Hyspalensem (?).

- Venice, Biblioteca Marciana MS. Lat. VI. 215. [3519.], anno 1475

Geber. Liber de inventione perfectionis. Liber Fornacum translatum. per

Rodericum Yspanensem.

- Ferguson MS. 232., 17th Century.

f72v-76 Geberi Arabis Philosophi sollertissimi rerumque naturalium

peritissimi, liber fornacum ad exerienda [...] pertinentium interprete

Rodogero Hispalensi.

- British Library MS. Sloane 1068. 17th Century

6.

Ejusdem 'liber fornacum, ad exercendam chemiam pertinentium; interprete

Rodogero Hispalensi'. f.369.

[Printed

Basiliae, 1561, p.193].

The name of the translator of Liber fornacum occurs also in the following printed Latin works:

Nürnberg 1541[8] (Fig 1)

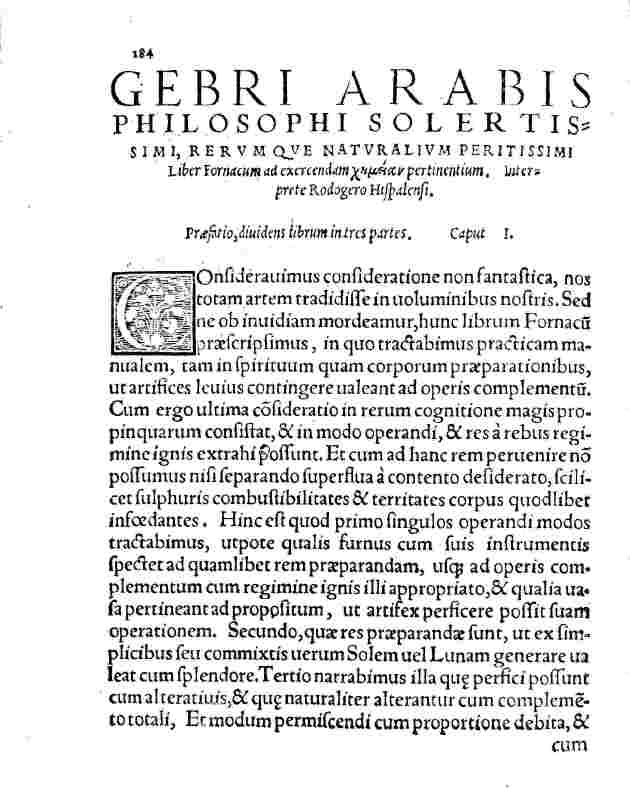

Bern 1545[9] (Fig 2)

Basiliae (Basel) 1561[10] (Fig 3)

We summerize:

1. Four Latin manuscripts of Liber fornacum and three printed editions mention the name of its translator from Arabic

2. According to Darmstaedter, the manuscript of Bologna, Italy, indicates the place of the translation in Spain and its date in the Arabic calendar (the Hijra).

3. With this important information the theory of a Latin Pseudo-Geber is severely challenged.

Figure SEQ Figure

\* ARABIC 2 Title page of Liber Fornacum in the Bern ed. 1545 with the

name of the translator

|

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 3 Title Page of Liber Fornacum in Basel Edition 1561 showing the name of the translator. |

[1] See Brief Notes at this web site.

[2] Darmstaedter, Ernst, Die Alchemie des Geber, , Berlin, 1922. Reprinted in Natural Sciences in Islam, Vol. 71, Jabir ibn Hayyan, III, edited by Fuat Sezgin, Frankfurt, 2002, pp. 69-298.

[3] Darmstaedter, Ernst,“ Geber Handschriften“, (Vorläufige Mitteilüng), Chemiker – Zeitung, (Cöthen) 48, 1924, pp 441-442 Reprinted in Natural Sciences in Islam, Vol. 71, Jabir ibn Hayyan, III, edited by Fuat Sezgin, Frankfurt, 2002, pp. 299-300.

[4] Interprete means translator

[5] The 1545 edition is that of Bern.

[6] We found it in the 1561 edition (Fig 3)

[7] Kopp, Hermann, Der Geschichte der Chemie, Drittes Stück, Braunschweig, 1875, p. 84.. Reprinted in Natural Sciences in Islam, Vol. 69, Jabir ibn Hayyan, I, edited by Fuat Sezgin, Frankfurt, 2002, pp. 36..

[8]

De alchemia.

a compendia volume

Petreus, Nurnberg. 1541. [8] + 373 + [5]

pages.

[9] Alchemiae libri, Bernæ: Mathias Apiarius, Ioannes Petreius excude faciebat 1545

[10]

Verae alchemiae artisque

metallicae, citra aenigmata, doctrina, certusque modus, ...Investigatione,

Summa, Inventione, Liber Fornacum

,

Bâle : Heinrich Petri et Pietro Perna 1561

Copyright Information

All Articles and Brief Notes are written by Ahmad Y. al-Hassan unless where indicated otherwise.

The design of this website does not belong to Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, the design was based on common webdesign elements.

All published material are the copyright of the author (unless stated otherwise) and may not be published or reproduced in part or in whole without the express written permission of the author.