History of Science and Technology in Islam

THE CULTURE AND CIVILIZATION OF THE UMAYYADS[1]

AND

PRINCE KHALID IBN YAZID

In

this essay we shall discuss the culture and the translation

activities in the Umayyad period. Orientalists adopted the thesis

that Arabic science started only with the translation movement that

took place with the reign of the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma'mun in the

ninth century CE. Therefore some historians in the West considered

the work of Khalid ibn Yazid as legendary or fabricated.[2] This

essay sheds new light on the civilization and culture of the

Umayyads and on the historic personality of Prince Khalid ibn Yazid.

1-

THE EMERGENCE OF UMAYYAD SCHOLARSHIP

The

Umayyad Arab-Islamic Empire

Islamic science arose in South-West Asia and Egypt. According to

Toynbee, this area remained the heart of the whole world, the Oikoumene,

for about four thousand years before Islam. With the rise of Islam,

and under the Umayyad and the Abbasid caliphates, the area

consolidated its position and remained the heart of the civilized

world. With the conquest of Iraq, Iran, Syria and Egypt, the Islamic

empire inherited the Sassanian and the Byzantine Empires and with

them all the ancient civilizations.[3]

The

Prophet started the message of Islam in Mecca and Medina, and the

call for Islam triumphed during his lifetime in Arabia. Abu Bakr was

elected as the first caliph in 11/632. `Umar succeeded him from

13/634 until 23/644. Within a few years during Abu Bakr's and `Umar's

caliphates, the Muslim Arabs conquered Syria, Iraq, Iran and Egypt.

During Abu Bakr's time the Arabs defeated the Byzantines at the

battle of Ajnadin in Palestine in 13/634. In 13/635, Damascus opened

its gates for the victorious Arab army. The decisive victory over

the Byzantines in Syria was achieved at the battle of al-Yarmuk in

15/636. Jerusalem surrendered in 17/638 and Caesarea in Palestine,

the last fortified post, fell in 19/640.

In

Iraq the Arab conquest was progressing in a parallel path. The major

victory of the Arabs over the Persians took place at al-Qadisiyya in

16/637. The Arabs took over the capital al-Mada'in (Ctesiphon) and

drove the Persian army outside the frontiers of Iraq. The fate of

Persia was decided at the battle of Nahawand in 21/642 after which

all Persian lands surrendered.

As

soon as Syria came under Arab rule, the Arab armies were directed to

Egypt. The main Byzantine army was defeated at Heliopolis in 20/640.

The conquest of Egypt was achieved without much difficulty.

Alexandria, the capital, surrendered in 22/642.

The

conquest of Syria, Egypt, Iraq and the Persian territories was

achieved during 'Umar's caliphate and he can thus be considered the

real founder of the Arab-Islamic Empire.

With

the rise of the Umayyad caliphate the Arab-Islamic conquests entered

their second phase. Within twenty years between 73/692 and 94/712

the Umayyads added North Africa, Spain, Sind and Transoxania to the

Arab-Islamic Empire. They, in effect, doubled the size of the

Empire, and before the end of their period a major portion of the

world, as known then, became part of the Arab-Islamic caliphate.[4]

Historians tried to give various reasons for this spectacular

victory which was achieved by the Arab armies. Among these are the

exhausting and weakening effects of the wars between the Sassanian

and the Byzantine empires.[5] But

whatever military or economic factors are cited, the main factor

indeed was Islam itself and the deep faith and zeal of its followers

to spread its message to the world at large. This desire to carry

the message of Islam created an international empire and resulted in

confirming Islam as an international religion, and in ultimately

creating an international culture which had a deep influence on the

course of human civilization.

Pre-Islamic roots of civilization

The

first phase of the conquests united the lands of the ancient

civilizations, the valleys of the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates along

with the other countries in the area. Here the first civilizations

in history arose and developed, and in this same area Islamic

civilization arose, flourished and reached its Golden Age. In the

new Arab-Islamic Empire the various elements of the Syriac,

Hellenistic and Persian civilizations were blended together and

formed a fertile compost out of which Islamic civilization grew and

blossomed. The old fire was not yet extinguished in its original

hearth when the Arabs conquered South-West Asia and Egypt; and with

the rise of the Arab-Islamic Empire the fire started to kindle again

with vigour at the hands of the Arabs, the new Muslim converts and

the Arabized population of the region .[6]

It

is not accidental that Islamic science arose and flourished in Iraq,

Persia, Syria and Egypt. The first beginnings of science and

technology in history took place in this area and from thence were

diffused east and west. The Sumero-Akkadian civilization is

estimated to have started about the fifth millennium BCE, and the

Egyptian in the fourth.

The

irrigation systems in Mesopotamia and in the Nile Valley were the

mainstay of all pre-Islamic civilizations; and the industrial and

technical skills in the cities in such products as textiles,

leather, glass, metalworking items and armaments were unmatched.

Here the trades and crafts were developed and were handed over from

one generation to the other, and so the inherent skills were deeply

rooted in the urban societies.

The

same can be said about science and culture in general. Science

started to develop with the onset of the ancient civilizations of

Mesopotamia and Egypt. This tradition continued uninterrupted.

The

Hellenistic civilization was principally a Near Eastern one which

flourished in this same area; and until the eve of the Arab

conquests, Iraq had been the power-house of the Sassanian empire,

and Syria and Egypt of the Roman empire and then of Byzantium.[7]

Because Islamic civilization had Islam as its motive force and

Arabic as its language, some historians considered this civilization

to be based on the pre-Islamic civilization of Arabia only. This led

them to consider the Syriac, Hellenistic and Persian cultural

elements as `foreign' elements in Islamic civilization.[8] Islamic

civilization is however the civilization of all the peoples who

became part of the new society. It had its roots in all the

pre-Islamic civilizations of the same area. Besides Islam and

Arabic, Syriac, Persian and Greek cultural elements, formed the

ancestral traditions of most of the Muslim population. Thus the

history of pre-Islam includes that of Arabia and of the lands

extending from the western Mediterranean to the Oxus or wherever

Islam was established.

The

Arab rulers did not disrupt daily life in the conquered areas. The

civil administration was maintained, the crafts, trades, industries

and agriculture continued as before. Even the original cultural and

religious institutions maintained their activities without

interruption. The conversion to Islam and to Arabic developed with

the passage of time and took a natural course. This policy helped

Islamic civilization to have its roots deeply embedded in a fertile

soil.

Non-Muslim centres of learning during Umayyad Caliphate

The

lands which were incorporated into the Umayyad Caliphate during the

first century of Islam possessed ancient centers of learning. By the

time the Arabs established their rule, these centers of learning had

already moved from Athens to Alexandria and, from thence to Antioch,

Edessa and Nisibis. It is also important to know that some esoteric

aspects of the Graeco-Alexandrian heritage had also found fertile

soil in the cult of the Sabaens of Harran who had developed their

metaphysics on the foundation of the Hermetic-Pythagorean ideas of

Alexandria and on the Babylonian and Chaldean traditions.

By

the time the Arabs arrived in Syria, the Syriac-speaking Christian

community had developed characteristic features of its own. In

contrast to the Hellenized Christianity of the coastal areas, which

used Greek Scriptures, the indigenous Semitic population used Syriac

for divine worship. Moreover, Syriac Christianity was more

monastic in its general practices than the Hellenized church.

In 363 CE the provinces of the Roman Empire east of the Tigris fell

to Sassanians and the Syriac Christian community to the east was cut

off from the Byzantine Empire and hence from the influences of

Antioch or Constantinople.

In

addition to Alexandrian Hellenism, the intellectual heritage of

Persians and Indians became simultaneously available to the Arabs.

During the Sassanid period, the Persian king Shapur I had

established a school at Jundishapur where Persian and Indian

scholars were active. By the seventh century, this school had

integrated the Greek, Persian and Indian sciences and was perhaps

unsurpassed in medicine and astronomy.

Muslim centres of learning during the era of the first four caliphs

and the Umayyad Caliphate

Arabic and Islamic sciences started to form with the appearance of

Islam and the completion of the Qur'an. We can consider the period

of the first four caliphs, `the Well-Guided Caliphs' (al-Khulafa'

al-Rashidun) (11-41 /632-661), and of the Umayyad caliphate

(41-133/661-750), to be the periods in which the foundations of

Islamic sciences were laid. During these two periods the message of

Islam was successfully launched and the Islamic Empire reached its

final frontiers. These are the periods which witnessed the formation

of the new Islamic society and the conversion of the peoples of the

old empires to Islam and to Arabic.

Medina was the seat of government during most of the period of the

first four caliphs. Here most of the Companions of the Prophet (al-Sahaba)

lived, and here Islamic sciences were initiated. Here also most

scholars of that period completed their studies in Hadith

(Tradition), fiqh (jurisprudence), tafsir (commentary on the

Qur'an), and history. Another school arose in Mecca, second in

importance to that of Medina.

After the conquests, a number of the Companions of the Prophet left

Medina for the new Islamic lands and they formed the nucleus of the

new schools which were established in these lands. Basra was the

oldest school to be established outside Arabia, and Kufa followed

shortly after. Both Basra and Kufa were newly built Arab cities

which gained prominence in the history of early Islamic culture.

Basra can be considered the crucible where all the elements of

Islamic culture were fused. It was established during 'Umar b. al

Khattab's caliphate between 14/635 and 17/638 in a strategic

location where sea and land communications meet. It was on the edges

of Arabia, Persia and Iraq. It started as a camp for Arab armies for

the eastern conquests and developed later into an administrative

capital for Khurasan and some eastern provinces. During the eighth

and early ninth centuries Basra became a great city with an

estimated population of between 200,000 and 600,000. In that period

it became an international centre for finance, commerce and culture.

Basra therefore possessed all the factors favourable for the rise

and the flourishing of culture. It was located in the heart of the

most populated and the richest parts of the Islamic Empire. It was a

meeting place for all ethnic elements of the empire. A fusion of

these elements in Basra was the starting point for the rise of

Islamic sciences and culture.

Kufa

was established one or two years after Basra on `Umar's orders. `Ali

chose it as his capital. It was also of great importance because of

its geographical position in Iraq, the richness of which was noted

above. Kufa became an important centre for a cultural movement and

was the rival of Basra in this respect. When the seat of the

caliphate moved to Damascus during the Umayyads, the new capital

also became an important cultural centre, in addition to Medina,

Mecca, Basra and Kufa.

During this first period, the philosophical and rational sciences

were still active, to a certain extent, in their original sites in

Alexandria, Jundishâpûr, and in the schools of northern Syria.

In

this first period the new society in the above cultural centres was

in the formative stage, and the foundations of Arabic, religious,

philosophical and rational sciences were being laid.

The

beginnings of Arabic and religious sciences

Immediately after the death of the Prophet in 12/633, Abu Bakr asked

Zayd b. Thâbit to collect the Qur'ân and to record it, and in

30/650-651, on the orders of `Uthman, Zayd completed the final

edition which has remained in use ever since. The recording of the

Qur'an was an event of great historical significance because it

heralded into human culture a new language which was destined to

remain the international language of science for several centuries.

The

importance which the new language assumed due to the spread of

Islamization and Arabization among non-Arabs led to the appearance

of Arabic grammar. It is reported that Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali (fl.

89/688) was the first to lay the foundations of this science in

Basra.

Al-Hajjaj

b. Yusuf al-Thaqafi (d. 96/714) was instrumental in developing the

school of Basra and he is said to have introduced into Arabic the

consonantal points and vowel marks.

Al-Khalil

b. Ahmad (d. 170/786), another scholar from Basra, compiled al-'Ayn,

which was the first dictionary in the Arabic language. He also

developed Arabic prosody. His pupil Sibawayh (d. 179/795), who was

of Persian origin, wrote the first systematic presentation of Arabic

grammar in al-Kitab (literally:

The Book). Sibawayh was a typical scholar from the new

Arabic-Islamic generation which replaced the pre-Islamic

communities.

Muslim scholars started at an early date the study of the Qur'an and

thus the sciences of readings and interpretation developed. In

addition to the Qur'an, scholars paid great attention to the sayings

of the Prophet and thus began the science of Hadith (Tradition). The

Qur'an and Hadith formed the basis on which fiqh (jurisprudence),

and Usul al-din (Fundamentals of Islam) were developed. All these

new religious sciences were studied in the schools of Medina, Mecca,

Basra, Kufa and Damascus.

In

this early period appeared Abu Hanifa al-Nu'man, who was born in

Kufa in 81/700 and died in Medina in 151/768. He is the founder of

the Hanifite School of jurisprudence, which is the oldest and the

most widespread of the four Islamic Orthodox fiqh schools. It is of

interest to know that Abu Hanifa's grandfather was a Persian, which

is an indication that the new Islamic society had already started to

bear fruit.

The

rise of sects and cultural movements during the Umayyad's Caliphate

It

was natural to see the appearance of some sects and cultural

movements within Islam. These sects and movements were often caused

by political factions, and in some cases they were purely

intellectual. Besides the followers of Orthodox Islam (Sunna), the .Shi'a

was the next Islamic party in importance and in numbers. The

Khawarij were among the oldest religious groups and from this

movement there remained the Ibàdis, who are followers of `Abdallâh

b. Ibad who lived in Basra around 61/680.

Among the religious and philosophical movements of intellectual

origin was the Qadariyya, which adopted the concept of freedom of

will. This movement appeared in Damascus. The Qadariyya was opposed

ro the Jabriyya or al-murji'a, the Determinist movement.

An

important intellectual movement, the Mu'tazila, appeared in Basra.

It is said sometimes that it was influenced by the Qadariyya, and

some maintain that the Mu'tazila was a continuation of it. One of

its founders was Wasil ibn

'Ata' (d. 131/748). The Mu`tazila played a prominent role in Islamic

thought, and the movement reached its zenith during the reign of al-Ma'mun,

in Baghdad.

Among the religious-political movements was al-Murji'a. It is

generally maintained that this movement accepted the rule of the

Umayyads, contrary to the Shi'a and al-Khawarij. The attitude of

al-Al-Murji'a was that of tolerance: and in this atmosphere of

tolerance lived Abu Hanifa, and this had some influence on his

teachings.[9]

It

seems that the appearance of al-Qadariyya, al-Jabriyya and al-Murji'a

in Damascus took place at a time when Christian religious schools

were flourishing. The Umayyad caliphs were tolerant towards

Christians and the followers of other religions, which encouraged

the dialogues between Christianity and Islam in Damascus. Christian

clerics were experienced in the art of dialectic, and Muslim

scholars were obliged in the dialogue with them to learn the same

philosophical reasoning and use the same dogmatic subtleties. In

this period appeared Yahya al-Dimashqi (John of Damascus) (d.

132/749) and Theodore Abu Qurra (Abucara). In his youth John was a

companion to Yazid, who became the second Umayyad Caliph, and later,

John became

a high government official in the Umayyad court. He adopted the

profession of his father and grandfather. John left dialectic essays

in which he compared Islam with Christianity; his essays reflect

those dialogues, which took place in Damascus between the scholars

of both religions.

Within the Christian Church itself there was a debate about fate and

free will, and about hell and the eternity of punishment. Similar

debate on these same subjects took place in Islamic theological

circles, which led to the appearance of the intellectual movements

just mentioned [10]

2-

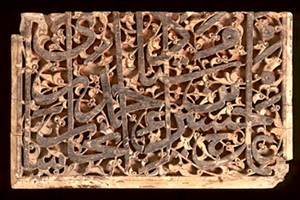

ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY OF THE UMAYYADS[11]

The

Arabization of the diwans, as we shall see later and the translation

of elementary scientific texts that are required for the kuttab of

the diwan is closely related to some aspects of Umayyad technology.

Unlike the theoretical sciences, architecture and technology do not

need a long period before they can flourish. Here

things were different. Hence the achievements of the Umayyad caliphs

in architecture and technology were prominent.

We

have pointed out that the new Islamic regions were the most advanced

in their civilization. In these regions arose the first and the most

important civilizations in history. Syria, Egypt, Iraq and Persia

were rich in their industries and agriculture. There were skilled

craftsmen, farmers and engineers. After the conquests, industrial

and agricultural production continued uninterrupted. The process of

conversion to Arabic and to Islam within the ranks of craftsmen and

farmers was taking place gradually without having any adverse effect

on their daily economic activities. On the contrary, the new

religion and the new state infused a new life into all aspects of

the economy and into all trades and crafts.

There was a large public sector under the direct control of the

state and large projects were undertaken.[12]

Early Islamic Cities and Umayyad Architecture

A

unique feature of Islamic civilization was its creation of new

cities right from the early period. 'Umar ibn al-Khattab built the

cities of Basra in 16/637 and Kufa in 17/638 as city camps for the

Islamic armies. These developed and grew until they became great

cities which influenced profoundly the political and cultural

history of Islam. 'Umar also built in Egypt the city of Fustat in

21/641-642. During the time of the Umayyads, `Uqba ibn Nafi' built

al-Qayrawan in North Africa in 50/670 during Mu'awiya's caliphate.

Sulayman ibn 'Abd al-Malik (97-100/715-718), built al-Ramla in

Palestine, and al-Hajjàj built Wasit in Iraq. The Umayyads also

developed and increased the size of several older cities.

The

building of new cities and the development of the old ones was

accompanied by the construction of an appreciable number of mosques

and palaces. The most famous of these buildings were the Dome of the

Rock and the Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, the Great Mosque in Damascus

and a series of palaces on the edges of the desert which were built

for the Umayyad caliphs or their sons.

The

construction of the Dome of the Rock was started by 'Abd al-Malik in

68/687 and was completed in 72/691. 'Abd al-Malik also constructed

the Aqsa Mosque which was rebuilt several times after that. The

construction of the Great Mosque in Damascus was started in 87/705

by al-Walid and it was completed in 97/715. These three

great mosques are still in existence and they retain till now their

original splendour.

Among the Umayyad palaces whose remains are in existence is

aI-Mashatta Palace south of Amman. It is one of the important

Umayyad palaces and was probably built by al-Walid II around

126/743. Another important palace is Qusayr 'Amra east of Amman. It

was built according to some historians during the caliphate of al-Walid

1 between 94/712 and 97/715 but other historians believe it was

built by Hisham ibn 'Abd al-Malik (106-126/ 724-743). It is famous

for its magnificent wall illustrations. The Khirbat al-Mafjar in

Jericho is considered the largest and the most beautiful among the

Umayyad palaces, and it was probably built by Yazid Ill in 127/744.

There are two great palaces which are also attributed to Hisham ibn

'Abd al-Malik; these are Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi and Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi.

They lie near the city of Palmyra (Tadmur). The Eastern Palace (al-Sharqi)

was built in 111/729 and the Western (al-Gharbi) in 110/728.

In

studying these early Islamic masterpieces of architecture one must

remember that the new Islamic lands were rich in craftsmen of all

trades. These craftsmen inherited the skills of the civilizations of

the Near East generation after generation, and they became an

important part of the new Islamic society. They however adapted

their skills to conform with the spirit of Islam and thus there

developed an Arabic or Islamic art and architecture.

The

same thing happened in all the other Islamic lands. And so different

schools of Islamic art arose in the various Islamic lands, which

were influenced by the inherited arts of the different regions.

About this early period we can say that Islamic architecture started

during the Umayyad period. The Umayyads left glorious architectural

monuments each with a unique Islamic style, and this Umayyad

architecture was a remarkable starting point from which later

Islamic architecture has developed [13]

Irrigation

Irrigation works and water distribution were very prominent among

the state's achievements. The Islamic religion considered these

among the chief duties of the state. When Basra was established

during 'Umar's period, he started simultaneously building some

canals for conveying drinking water and for irrigation. Al-Tabari

reports that 'Utba ibn Ghazwan built the first canal from the Tigris

River to the site of Basra when it was in the planning stage. After

the city was built, 'Umar appointed Abu Musa al-Ash'ari as the first

governor. Al-Ash'ari governed during the period 17-29/638-650. He

began building two important canals linking Basra with the Tigris

River. These were al-Ubulla River and the Ma'qil River. The canals

were completed under the later governors and thus Basra obtained the

necessary drinking water, and the two canals were the basis for the

agricultural development for the whole Basra region. 'Umar also

devised the policy of cultivating barren lands by assigning such

lands to those who undertook to cultivate them. This policy

continued during the Umayyad period and it resulted in the

cultivation of large areas of barren lands through the construction

of irrigation canals by the state and by individuals. Al-Baladhuri

gives the names of several canals which were constructed during this

period to cultivate barren lands.

The

various governors who were appointed by the Umayyads constructed

several works to prevent the formation of new swamps and to dry old

swamps, through the building of dams which regulated the flow of

water.

We

find in the original Arabic sources much detail about the irrigation

works which were constructed in Iraq in the regions of Basra, Kufa,

Wasit, al-Raqqa and several other areas. Al-Hajjaj was particularly

active in constructing irrigation works and the later governors

followed his policy.

One

of the Umayyad caliphs, Yazid ibn Mu'awiya, was so interested in

irrigation projects that he was called al-Muhandis, `the Engineer'.

In addition to his interest in the irrigation works in Iraq he

improved the water distribution canals of the Barada River in

Damascus. One of these canals, Nahr Yazid or the Yazid River, still

carries the name of that Umayyad caliph in commemoration of his

great service.

The

caliphs and the governors utilized in these irrigation works the

hereditary skills of the people of Iraq. The Nabataeans for instance

were skilled in agriculture and in irrigation works, and among the

great engineers who worked under al-Hajjâj to drain the swamps in

southern Iraq was Hasan al-Nabati (the Nabataean).

Norias (al-nawa'ir), or the large water-wheels which were driven by

the flow of water and raised water to a greater height, were used on

large scale on the Tigris and the Euphrates. They were used also on

the Orontes (al-'Asi River) and on al-Khabur River which is a

tributary of the Euphrates River. The saqiya, or the animal-driven

pot wheel, was also used extensively.

For

power purposes the water mill was also well established. The first

mention of the windmill in the Islamic period occurs during 'Umar's

caliphate, when Abu Lu'lu'a told 'Umar that he could build an

air-driven mill.[14]

Industrial chemistry

Numerous trades and crafts of the Umayyads are of the industrial

chemistry type. We shall mention some of them only.

The metallurgy of gold and silver –the

mint

Abd

al-Malik ibn Marwan decided to mint the Arabic dinar and to liberate

the economy from dependence on the Byzantine dinar and on the

Persian one. This took place in 76/695 following the Arabization of

government records. This financial reform had far-reaching

consequences and it is considered one of the major achievements of

the Umayyads. The Islamic gold dinar abolished the Byzantines'

monopoly of golden currency. The economy of the Islamic countries

was thus liberated and a new era of Islamic financial supremacy on

the international scene was established. The appearance of the

Islamic gold dinar and the silver dirham implied the adoption of

elaborate measures in the mining of gold and silver and in strict

and effective controls of the mint and of the circulation of coins.[15]

The

mint of the Arabic dinar required that part of the duties of the

administrator of the public treasury (bayt al-mal) was to see

to it that the right proportion of gold is cast in the minted

dinars, together with what all that implies by way of managing

alloys, composition of metals, and exacting weights and measures.

Such functions included some alchemy which was then called 'ilm

al-san'a , that was

being sought by Khalid ibn Yazid.

We are told by Abu Hilâl al-'Askari (c. 1000) in his kitab

a!-awa'il that:

"Abd

al-Malik ibn Marwan started to write surat

al-ikhlas (Qur'an,

112) and the mention of

the prophet on the dinars and dirhams, when

the king of Byzantium wrote to him the

following message: 'You have introduced in your official documents (tawamir) something

referring to your prophet. Abandon it, otherwise you shall see on

our dinars the

mention of things you detest.' That angered Abd al-Malik, so he sent

for Khalid

ibn Yazid ibn Mu'awiya, who was greatly learned and wise, in order

to consult with

him upon this matter. Khalid then told him, 'have no fear o

commander of the faithful!

Prohibit their dinars and

strike for the people new mint with the mention of

God on them, as well as the mention of the Prophet, may prayers and

peace be upon him, and do not absolve them of what they hate in the

official documents. And so he did!"[16]

The metallurgy of iron and steel

The

iron and steel industry existed in Damascus before the Arabs had

arrived, and Damascenes

swords were renowned throughout the Roman Empire.

The

composition of steel was first described by Jabir ibn Hayyan, and at

later dates by al-Kindi and al-Biruni. The dus,

a component of steel, was a main material in alchemical treatises

such as in the works of al-Razi.

Al-Biruni

gave a quotation from a book written by a Damascene ironsmith called

Mazyad ibn 'Ali. Mazyad gave a description for making crucible

steel. Al-Biruni says that Mazyad's book gives details of swords

that were described in al-Kindi's treatise on swords. We understand

from al-Biruni's statement that Mazyad ibn 'Ali lived in Damascus

before the time of al-Kindi. And since al-Kindi flourished in the

ninth century in Baghdad, it is reasonable to assume that Mazyad ibn

'Ali lived during the time of the Umayyad Caliphate in Damascus. [17]

Recipes for lustre glass

Lustre-painting, which is characteristic of Islamic glass and

pottery, is a metallic sheen applied on the surfaces of glass or

pottery objects. Its origin has been the subject of discussion

amongst historians, the suggested centres being, Syria, Iraq, Egypt

or Iran.

According to the latest reported archaeological finds, the earliest

existing examples of lustre glass were of Syrian origin during the

Umayyad period.(660–750).[18]Numerous

Umayyad glass lustre fragments have been found at Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi[19] that

was built in (728–9) by the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd

al-Malik, who ruled between 723 and 742. In addition, the glass

found at the ancient site of Pella[20] in

Jordan included Umayyad lustre-painted and gilded fragments.[21]

Since lustre glass was used in Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi, it is

reasonable to assume that the technique of lustre painting was

developed in Syria at an earlier date in the same century or even

before. This assumption seems reasonable because Jabir, who was

writing in the second half of that century, gave a large number of

recipes for this art, some of which may have been formulated by him

and some may have been compiled from previous practice. The

accumulation of such a large number of mature recipes requires

several decades of industrial experience.

Apart from these early fragments of Umayyad lustre glass, an extant

lustre painted glass cup from Fustat is dated 163/779 and another

cup from Damascus is dated 170/786.[22]

Books on gemstones

Al-Biruni

mentions in al-Jamahir that

he had acquired a book written in Damascus during the caliphate of

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan. The book deals with the qualities of

gemstones and their values. Al-Biruni says that according to this

book the red ruby and the good quality pearls were of equal value at

that time.[23]

Industrial recipes in general

Al-Biruni's

reports are of utmost importance. They confirm that there were books

from the Umayyad period about iron and steel and about gemstones.

Most of these Umayyad books were lost but we find also in al-Fihrist of

ibn al-Nadim the titles of several books whose authors are not

known.

Jabir's recipes were either inherited or developed. For recipes that

were not developed by him, he alluded sometimes to their sources,

and that he collected some of them. He says for example that he took

a waterproofing recipe from Al-Fadl ibn Yahya ibn Barmak who also

took it from a manuscript of unknown author, since the first pages

and the last ones were missing. Moreover, when Jabir describes the

manufacture of the adrak gemstone,

he says that he took it from a valuable manuscript. [24]

The recipes of Jabir that he gave in Kitab

al-durra al-maknuna and

in Kitab al-khawass

al-kabir and in other

practical works, are taken from earlier books of recipes.[25] And

since Jabir flourished in the eighth century, his sources must

belong to the Umayyad period.

The

weapons industry

During the early Arab conquests the weapons of war consisted of

light weapons which comprised mainly the sword, the lance and the

bow and arrow. These weapons were made in Arabia, and the different

kinds of swords, lances and bows carried the names of the places

where they were made. After the conquests of Syria, Iraq, Egypt and

Persia the technical skills of these countries in the manufacture of

weapons had enhanced greatly the capabilities of the Islamic weapons

industry. Damascus for instance was famous before Islam in the

manufacture of weapons and of steel blades and this fame had

increased greatly after Islam.

From

`Umar's time, the state undertook to provide the regular soldiers,

who were unable to secure their own weapons, with the necessary

equipment. Such weapons which were supplied by the government were

specially marked. 'Ali established the armouries or weapons

warehouses (khaza'in al-silah), and he marked the government's

weapons with special signs.

Besides light weapons, the Islamic armies used siege equipment,

especially the manjaniqs (catapults). It is reported that the

Prophet used the manjaniq in his siege of al-Ta'if. It is reported

also that some Companions of the Prophet received in Jerash some

training in the construction of manjaniqs and other siege engines.

The use of these machines by the Islamic armies increased during the

conquests of Iraq, Syria and other countries.

The

construction, operation and maintenance of siege engines was the

government's responsibility from early Islamic times. It is reported

that 'Amr b. al-'As constructed manjaniqs upon his arrival in Egypt

and he used them in Egypt's conquest. The use of these siege engines

increased during the Umayyad period. Marwan b. Muhammad

(127-32/744-49), the last of the Umayyad caliphs, in his siege of

Homs in 127/744. used more than eighty manjaniqs according to Ibn

al-Athir.

Military fires

The

use of military fires was known to the Umayyads. In 64/683 al-Ka'ba

was bombarded by stones, naft and other combustible burning fires.

Military fires were used also by the Islamic fleets in the

Mediterranean during the Umayyad campaigns.

The

use of naft by the Umayyads was a natural development. It should be

remembered that chemical technology had reached an advanced stage in

the area in pre-Islamic times. Even the Greek fire which was used by

the Byzantines was brought to them by the Syrian engineer,

Kallinicus, who fled from Baalbek in Syria to Constantinople in

59/678 during the Umayyad period. Kallinicus was brought up in Syria

during the Islamic era where he received his training in chemical

technology.[26]

Dar

al-Sina'a and the Islamic fleets

One

of the major achievements of 'Uthman b. 'Affan was the creation of

the first Islamic naval power. But a great deal of credit should go

to Mu'awiya, who pursued this objective when he was governor of

Syria during 'Uthman's caliphate and after he became caliph himself.

Mu'awiya realized that Arab-Islamic rule in Syria and the other new

Islamic Mediterranean countries could not be consolidated without an

Islamic naval power which could repulse the Byzantine naval attacks.

The policy of Mu`awiya was followed by his successors, and Islamic

naval power enabled the Umayyads to continue their conquests until

all of North Africa and Spain came under Islamic rule.

During 'Umar's caliphate, Mu`awiya established the ribat system. The

ribats were fortresses built near the coastal cities in which

military forces were kept to defend these cities against the

Byzantine attacks. They served also as shelters for people during

such raids.

These fortresses contained rooms and lodgings for the soldiers,

armouries, storage for food and observation towers. Later on, the

ribat developed into bases for undertaking naval campaigns.

During 'Uthman's caliphate the governor of Egypt, 'Abdallah b. Abi

Sarh, started the building of naval ships in Egypt, utilizing the

skills of Egyptian craftsmen. The close cooperation between Mu`awiya

and Ibn Abi Sarh enabled the Muslims to occupy Cyprus in 28/649, and

Rhodes in 33/654. In 34/655 the combined Islamic fleet of Syria and

Egypt defeated the Byzantine

fleet near the coast of Lycia in the Battle of the Masts (Dhat al-Sawari).

This battle was a fatal blow to Byzantine naval power and it

heralded the beginning of Islamic supremacy in the Eastern

.Mediterranean.

Mu`awiya became caliph in 41/661. In 49/669 he chose `Akka (Acre) as

a site for the first dar al-sina'a (arsenal or shipyard) in Syria.

He recruited for this purpose craftsmen and carpenters from various

places in Syria. During Mu'awiya's caliphate the Islamic fleet

besieged Constantinople twice, in 49/ 668 and during the seven

years' war between 54/674 and 60/680.

The

strongest siege of Constantinople took place in 98/716 during the

caliphate of Sulayman ibn 'Abd al-Malik. The Islamic fleets from

Syria, Egypt and North Africa participated in this siege and the

Arabs used military fires and some types of artillery.

The

Umayyads adopted the same policy in North Africa. Hassan aI-Nu`man

was appointed in 76/695 as governor by 'Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan and

he established a naval base in Tunis with a shipyard. He was

succeeded in 79/707 by Musa b. Nusayr, who continued the policy of

his predecessor in the building of naval ships. During Nusayr's

period as governor, Spain was conquered and the Islamic fleet played

a major role in that historic campaign: [27]

Al-tiraz

High-quality textiles were manufactured in state factories known as

tiraz. Such

textiles were woven for caliphs and high officials and were

presented to important persons. Textiles included the linen fabrics

of Egypt and the silk and brocade cloths of Damascus. The caliphs

established the tiraz factories in their palaces which were managed

by the sahib al-tiraz who was in charge of spinners and weavers,

paying their wages and controlling the quality of their work.

Al-tiraz

factories acquired great importance under the Umayyads and they

continued in importance during the Abbasid period. `Abd al-Malik

changed the inscriptions on the borders of the tiraz textiles into

Arabic-Islamic writings. Before that the tiraz inscriptions followed

Byzantine, Sassanian or Coptic traditions.

Papyrus (al-qaratis)

Al-qaratis

were used for writing. They were manufactured in Egypt out of

papyrus. This industry was also under state control. 'Abd al-Malik

replaced the Coptic signs on the qaratis by Islamic writings. The

use of the qaratis continued until paper factories were established

during the Abbasid period

The

mail service (al-barid)

`Abd

al-Malik also established a mail service, al-barid, connecting the

far regions of the vast empire with each other. This system was

utilized by al-Walid and the other succeeding caliphs in undertaking

and organizing several important projects. Al-barid continued to

increase in importance during the Abbasid caliphate.

3-

ARABIZATION OF THE ADMINISTRATION AND THE START OF TRANSLATION

Arabization of the diwans

Without the arabization of the administration by Abd al-Malik ibn

Marwan the translation movements that followed, including that of

Bayt al-Hikma in Baghdat in the ninth century, could not have taken

place. This Arabization of the administration by the Umayyads was a

crucial step towards making Arabic the language of culture

throughout the whole empire.

The

translation of the diwans from Greek into Arabic in Syria took place

during the reign of the Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan under his

personal supervision. They were translated from Persian to Arabic in

Iraq and beyond by al-Hajjaj the governor of Abd al-Malik. In Egypt,

the diwans were translated from Coptic into Arabic by Abd al-Aziz

ibn Abd al-Malik the governor of Egypt.

The

historic arabization reform of Abd al-Malik took place at the same

time when Khalid ibn Yazid undertook the translation of scientific

works from Greek into Arabic. Khalid

was greatly respected and esteemed by the Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn

Marwan, and he advised the caliph on the mint of the Arabic dinar

and the arabization of the administration.

The

diwan operations dealt with accounting procedures which required

handling arithmetical operations carried over fractions and the

like.[28] Therefore

the diwan that needed translation into Arabic was the diwan in which

such complicated operations were performed. Therefore, the diwan

that was translated into Arabic was the diwan of revenues, and

revenues were the backbone of any government then, as now

Since procedures dealing with revenues required arithmetical

operations for such functions as the surveying of real estates, a

diwan officer, as a revenue collector should have the qualifications

to carry out those procedures.

Furthermore, the computation of time in solar years, when taxes

should be paid, is not always easy to calculate without some

elementary astronomical knowledge. That too must have forced the

diwan officer to learn some astronomy. Elementary operations

involved also the re-allocation of payments, especially after the

distribution of inheritance, the digging of canals, etc., all of

which necessitated that the said officer acquire such computational

skills. for which Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi had to compose a

complete book on Algebra just for that same purpose.

The

operations which a diwan officer was supposed to perform were not

easy, and there must have been some elementary texts or manuals that

were used to train those who worked in the diwan.

We

do find in the work of Ibn Qutayba (d. 879) who himself was a

contemporary of the last period of translation that followed the

translation of the diwan, a short synopsis of the qualification of

those who sought employment in the diwan, or those who were then

called kuttab. Those kuttab were undoubtedly the heirs of the diwan

employees.

In

his book Adab al-katib,

Ibn Qutayba stresses that the katib must seek the following

sciences, if he were to be worthy of the name katib, and not be

among those who are after the office of katib in name only:

"He

must-in addition to our books, investigate matters relating to land

surveying, so that he would know the right angled triangle, the

acute, and the obtuse angled triangle; the vertical plumb lines (masaqit

al-ahjar), the various squares (sic), the arcs and the curves, and

the vertical lines. His knowledge should be tested on the land and

not in books, for the one who reports is not like the eyewitness.

And the non-Arabs ('ajam) used to say: 'whoever was not an expert in

matters relating to water distribution (ijra' al-miyah), the digging

of trenches for drinking water, the covering of ditches, and the

succession of days in terms of length increase and decrease, the

revolution of the sun, the rising of the stars, the conditions of

the moon when it becomes a crescent as well as its other conditions,

and the control of weights, and the surface measurement of the

triangle, the square, and the polygons, the erection of arches and

bridges as well as water lifting devices and the norias by water

side, and the conditions of the artisans and the details of

calculations, he would be defective in his crafts"

Working in the diwans, as far as Ibn Qutayba could ascertain, should

include a mastery of all those sciences that were just listed by

him. This must mean that the diwans that were translated must have

included the elementary texts of those sciences. For it was quite

unlikely that Ibn Qutayba would call on the kuttab of his time to

acquire these sciences if there were not any texts through which

they could be acquired.

Another confirmation of the sciences needed for the kuttab of the

diwan comes from another scientist who was also interested in the

education of the kuttab and government bureaucrats. Several of his

books have reached us from about the middle of the tenth century.

The author in question was the famous scientist, Abu al-Wafà' al-Buzjani

(d. 998), whose name was very closely associated with the Greek

mathematical and astronomical works that were translated into

Arabic. It was this Abu al-Wafa' who had left us two books which

directly address the geometric and arithmetical needs of the

artisans and workers (obviously including government employees),

that were called: What

the Artisans need by way of Geometry, and What

the workers and kuttâb need by way of Arithmetic [29].

In both of these texts, Abu al-Wafa' takes up elementary

mathematical problems, of the types that were obviously discussed in

the diwans of his time, or among those who were employed in those

government departments who were then learning how to carry out the

new functions that required those new sciences.

These examples are intended to confirm the meaning of the diwan that

was arabized by Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan. We conclude that the

translations of the Persian and Greek diwans into Arabic must have

included a group of elementary scientific texts. To embark on such

an ambitious arabization program, the Umayyad government of Abd al-Malik

must have provided manuals for such elementary sciences for its

employees in order for them to function in an efficient manner.

4-

RATIONAL SCIENCES OF THE UMAYYADS

If

we contemplate the history of any civilization from its beginning,

to its climax and then to its decline, we shall realize that nations

were interested only in those sciences that are required for their

daily needs, and they gave attention

to advanced theoretical sciences after a long time only. In Islamic

civilization attention was directed first of all to medicine,

astrology and alchemy.[30]

Philosophy

We

have discussed the appearance of the Islamic intellectual movements

and the debates which took place among Muslim scholars themselves

and between them and Christian scholars in Damascus under the

Umayyad caliphs. To acquire the necessary tools for these debates

Muslim scholars turned eagerly to study the philosophical and

logical tools which were employed by their opponents. Logic as a

tool in discussions and arguments was especially important. Our

knowledge about the philosophical books that were translated into

Arabic during the Umayyad period is limited. But we learn from Ibn

al-Nadim that Thawon may have translated Categories: from Syriac

into Arabic. Istfan is also mentioned as a translator for Khalid ibn

Yazid and he may have translated Categories.

Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik paid great attention to translation. Ibn al-Nadim

mentions that Salim Abu al-'Ala' the katib or secretary of Hisham

translated for him the episles of Aristotle to Alexander. Al-Mas'udi

reports also that Kitab

siyasat al-furs (Policies

of the Persians) was translated for Hisham. This is a great book

which contains many of the Persian sciences, the tales of their

kings, their buildings and their policies. [31]

Beside these translations of the caliphs there were individuals who

sponsored some translations for their own personal use.

Medicine

Said

b. Ahmad al-Andalusi says in his book Tabaqat

al-umam (Classification

of Nations) that `the Arabs at the dawn of Islam paid attention only

to their language and to the aspects of Islamic law, with the

exception of medicine which was practiced by some individuals and

was appreciated by common people because everybody was in need of

it.' [32]

The

Prophet spoke about medicine, health, illness, protection against

infection and the merits of physicians. There are about one hundred

sayings of the Prophet discussing these topics which were collected

and are referred to as al

tibb al-nabawi (the

medicine of the Prophet). The Prophet also encouraged people to

consult the physicians.

The

most prominent Arab physician during the Prophet's period and during

Abu Bakr's caliphate was al-Harith b. Kalada, who was called the

Physician of the Arabs. It is reported that he died in

11-13/632-634. It seems that al-Harith studied medicine in

Jundishapur and he was familiar with medical books either in Greek

or Syriac or both. Some reports claim that al-Nadar b. al-Harith b.

Kalada succeeded his father as a physician.

When

Damascus became the seat of the Umayvad caliphs they relied on the

physicians of the new Islamic countries who studied medicine at

Alexandria, Antioch and Jundishapur, which were the cultural centres

for the study of the rational sciences, especially medicine. At that

early period most physicians were Christians because the conversion

movement to Islam was in its early stage. We see here however the

first beginnings of translation of medical works into Arabic.

Among the physicians of the Umayyads were Ibn Athal, Mu`awiya's

physician, and Abu al- Hakam al-Dimashqi who served under Mu`awiya

and several later caliphs. One of the prominent physicians of this

period was Tayadhuq, who was the physician of al-Hajjaj. Tayadhuq

wrote three or four medical books which have not come down to us.

Another prominent physician from Basra was Masarjawayh, who was a

Jew from Persia. He translated from Syriac into Arabic a medical

book written originally in Greek by Ahron (or Ahren). It is possible

that this was the earliest translation into Arabic of a medical work

that had a Greek origin. The

Arabic title is al-Kunnashwhich

means in Syriac '

a medical summary'. This book contained thirty chapters. The author

Ahren lived in Alexandria during the reign of Hiraql (Heraclius) in

the period 610-641. It was translated into Syriac and was popular

among the Syrians.

The Kunnash was

translated during the reign of Marwan ibn al-Hakam, 64/784 – 65/685.

Ibn Abi Usaybi'a mentions in 'Uyun

al-anba' fi tabaqat al-atibba' that

the Caliph 'Umar ibn 'Abd al-Aziz found this book in the libraries

of Damascus and he ordered that it should be made public and be

accessed easily by the general public.[33]

Among the physicians of this period also was `Abd al-Malik ibn Abjar

al-Kinani, who was teaching medicine in Alexandria, and was a

physician to `Umar ibn `Abd al-`Aziz when the latter was governor of

Egypt. When `Umar became caliph, he invited him to move to Syria,

and thus the teaching of medicine moved to Antioch.

The

first hospitals in Islam

It

is important to mention in this brief survey that the Umayyads

established the first hospitals in Islam. The first proper hospital

was established by al-Walid ibn 'Abd al-Malik (d. 96/715). In this

hospital patients affected with leprosy were isolated in special

quarters and received special care.

Astronomy and astrology

Important astronomical activities were still going on in Syriac

during this period. Syriac scholars were still active in writing in

Syriac and in translating from Greek into Syriac. Among these

scholars was Severus Sebokht, who was born in Nisibin and lived in

Qenneshrin (Qinnisrin) near Aleppo. Sebokht flourished in the middle

of the seventh century and wrote a treatise on the astrolabe and

wrote on other astronomical subjects. Another scholar was George,

bishop of the Arabs (d. 106/724) who lived in upper Mesopotamia and

was bishop of the Arab tribes. He composed a poem on the calendar.[34]

The

first effect of Islam on astronomy was the adoption of the lunar

calendar for Islamic history which starts on 15 July 622. In more

than one verse, the Qur'an urges Muslims to study astronomy. For

practical purposes also Islam had a great influence on the

development of this science when astronomers worked actively in

compiling astronomical tables and in determining the direction of

al-qibla from various geographical locations.

There are reports on translations of astrological and astronomical

works into Arabic in this period. Khalid

ibn Yazid ordered the translation of some works on astrology.

The Umayyads showed clearly an interest in Greek astrology and

astronomy. The little Umayyad audience hall and bath of Qasr 'Amra, located

in present-day eastern Jordan around

A.D. 711, contains on the inside of the dome, a painted

representation of the zodiac made on a stereographic projection.

A

book on astrology that was translated from Greek unto Arabic was Kitab

'ard miftah al-nujum which

is attributed to Hermes. A copy of it is found in Milano at the Ambrosian

Library. At the end of the manuscript it is written that the

translation was made in Dhi al-Qi'da in 125/743.

There

were arguments by Muslim astrologists in support of the practice of

astrology including the use of court astrologers by the Umayyad

caliphs. The Islamic ruling on horoscopes is that they are

forbidden.

In

spite of this the Umayyad Caliphs and the governors of the realms

used to consult astrologers. It

is reported by al-Mas'udi that Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (the

contemporary of Khalid ibn Yazid) was fond of astrology and that he

used to have in his company some astrologers during his campaigns.[35]

Similarly Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf al-Thaqafi consulted astrologers and

he had his own astrologer. There are some historic stories about al-Hajjaj and

astrologers.

.

One

story is about the astrologer of al-Hajjaj. Al-Hajjaj placed in his

hand some pebbles of known number. He asked the astrologer, tell me:

how many pebbles do I have in my hand? The astrologer made some

calculations and he gave the correct answer. Then al-Hajjaj, without

letting the astrologer notice him, took

in his hand a quantity of pebbles which he did not count. The

astrologer made some calculations and he gave the wrong answer. He

repeated his calculations but the answer was still wrong. Then the

astrologer said: O prince, I think that you do not know how much is

in your hand. Al-Hajjaj said, no. but what is the difference? The

astrologer answered; the first pebbles were counted by you and they

were outside the realm of the un-known, The second pebbles were not

counted and they remained in the realm of the un-known. And only God

knows what is in the realm of the un-known.

Umayyad scholars and scientists who continued during the early

Abbasid period

The

early Abbasid caliphs relied on physicians, astrologers, alchemists

and other scholars of the Umayyad period who were already

accomplished.

The

Islamic scientific community had already entered the formative

stage. Syriac scholars became versed in Arabic as a result of Abd

al-Malik ibn Marwan's arabization of the administration and of

adopting Arabic as the language of culture and science. Persian

secretaries and employees of the diwans were obliged to use Arabic

only. The

academic community in Jundishapur adopted Arabic also beside the

other languages of Persian, Syriac and Greek.

There were workshops established in Iraq and Persia to train

secretaries in working with Arabic.[36] Apart

from secretaries, it seems that there were avenues by which

astronomers and

astrologers were given a thorough training either through individual

tutoring or by receiving their training in groups.

One

of the scholars who lived most of his life under the Umayyads was

Abd allah ibn al-Muqaffa' who was born in 720 in Jur in Fars and

died in 756 at the age of 36 in al-Basra.

Ibn

al-Muqaffa's father was one of Umayyad secretaries in Iraq and ibn

al-Muqaffa', the son, was

trained as a secretary also, and served under the Umayyads.

Ibn

al-Muqaffa' was one of the Persian aristocratic class of secretaries

and he was involved in politics. Most of his literary work was

written during the Umayyad period. And during the Abbasid period he

was involved in the struggle for the caliphate between the

contenders. This led to his execution by Abu Ja'far al-Mansur.

Ibn

al Muqaffa's translation of Kalīla

wa Dimna from Middle

Persian is considered the first masterpiece of Arabic literary

prose. The translation was done while he was still an Umayyad

official.

During his years in Fars and Kerman as an Umayyad official, Ibn al-Muqaffa'

had time for his remarkable intellectual activity, and may well have

organised a translation workshop. [37]Whether

or not there were schools of translation in Damascus during the

Umayyads' rule, is open to question

Beside Kalila and

Dimna, an important book of maxims on government known as the

Covenent of Ardashir was translated by an unknown translator, while

Ibn al-Muqaffa' had translated the Letter

of Tansar. These

translations were made for the benefit of the Umayyad caliphs.

Ibn

al-Muqaffa; was a zindiq, namely a follower of the Manichaean

religion and he wrote treatises on this religion. He converted to

Islam in the last years of his life during the Abbasid period on the

request of 'Isa ibn 'Ali for whom he served as his secretary.

When

the caliph al-Mansur wished to build the city of Baghdad, in 762 CE,

he selected three astrologers and charged them with casting the

horoscope for the future city. [38] The

horoscope itself is preserved in the Chronology of

Biruni and in several other sources. Most sources agree that the

astrologers who were assigned that task included Nawbakht the

Persian (679-777) who

became the ancestor of the Nawbakht family of astrologers, which

served caliphs for a whole century, Ibrahim al-Fazari

(d. 777), and Masha'allah al-Farisi. Ibrahim al-Fazari was obviously

an Arab from the tribe of Fazara Al-Biruni

states explicitly that it was al-Nawbakht who determined the day for

the foundation of the city to coincide with the propitious 23rd of

July of that year.

We

may ask: where did these three astrologers acquire the kind of

advanced astronomical knowledge that they would have needed for

casting such a horoscope at that early time of Abbasid in power?

Another scientist was Ya'qub ibn Tariq who was a collaborator of al-Fazari,

and we may also ask where did ibn Tariq learn his own astronomy so

that he could produce, together with Fazari, a translation of the

Sanskrit Sidhanta (al-Sindhind),

which was completed during the caliphate of al-Mansur (754–775 CE).

Later sources always joined those two names together, so it is

sometimes difficult to determine who did what.

All

these astrologers may have learned their craft in Persia during the

Umayyad caliphate. But the sources are silent on that, and we do not

know much about the Persian astronomy of the time beyond the

existence of the Shariyar

zıj. Furthermore, the

historical sources report that al-Fazari and/or Ibn Tariq wrote a

theoretical astronomical work called Tarkib

al-aflak, which seems

to have been lost. The same Fazari is also credited with the

authorship of his own zij, in

which he used the “Arab years” ('ala sinıy

al-'Arab). Writing

a theoretical astronomical text, transferring a zıj to

a different calendar, and producing astronomical instruments such as

astrolabes -as we are also told about these men - could not have

been done by amateur astronomers. Who educated al-Fazari and Ibn

Tariq in all these fields of astronomy? And even if we believe that

the three astrologers also used the Persian Zıj-i

Shahriyar for the

purposes of the horoscope, we should also ask about another Arab,

_'Ali ibn Ziyad al-Tamimi, from the tribe of Tamim, who was supposed

to have translated this zij into

Arabic. Who taught al-Tamimi how to translate a zij, and

when he did so did he also transfer it into Arab years (as we are

told that al-Fazari had done)?

All

this evidence indicates that there was a class of people, who were

already in place by the time the Abbasids took over from the Umayyad

dynasty, who were competent enough to use sophisticated astronomical

instruments, to cast horoscopes, to translate difficult astronomical

texts, and to transfer their basic calenderical parameters, as well

as to compose theoretical astronomical texts such as Tarkib

al-aflak. Such

activities could not have been accomplished by people who were just

learning how to translate under the earliest Abbasids, as the

classical narrative claims.[39]

We

may mention here Jurjis,

the father of Bukhtishu II and grandfather of Jibril ibn Bukhtishu,

who was a scientific writer and was the director of the hospital in

Jundishapur, which supplied physicians to courts in Iraq, Syria, and

Persia. Due

to his medical renown, he was called to Baghdad in 765 CE to treat

the Caliph

al-Mansur. After successfully curing the caliph, he was

asked to remain in attendance in Baghdad, which he did until he fell

ill in 769 CE.[40] Members

of the Bkhtishu' family served the Abbasid caliphs during the ninth

and tenth centuries.

Masawayh, also a physician in Jundishapur, during the 8th century,

became the personal physician of Harun al-Rashid.

Theophilus al-Rahawi was the most eminent scholar among the

Maronites. He was active under the Umayyads and was later the chief

astronomer of the Abbasid Caliph, Al-Mahdi until his death in 783.

Al-Bitriq lived during the caliphate of al-Mansur (754-775), who

commissioned him to translate numerous ancient medical and

astrological works. One of his translated works is the Quadripartus

of Ptolemeus, Kitab al-maqalat al-arba'a in astrology.

5-

ALCHEMY AND PRINCE KHALID IBN YAZID

Alchemy, like medicine and astrology, was one of the sciences which

received attention at an early date. According to Ibn al-Nadim, the

Umayyad prince Khalid b. Yazid (d. 85 or 90/704 or 708) started the

first translation movement in Islam. He ordered the translation of

books on alchemy, medicine and astrology from Greek and Coptic into

Arabic. The importance of Khalid, however, is due to his alchemical

achievements. There are several alchemical treatises that are

attributed to him[41].

Due

to the doubts that were cast on Khalid and his work by Ruska and

others, we shall investigate his identity in some detail.

Alchemy and its public image

The

popularity of alchemy as a means of transmuting base metals into

gold continued after the rise of Islam. Adepts

of alchemy were already active at the time of the Prophet and under

the Umayyad dynasty (661–750). We shall see presently that

transmutation in alchemy had intrigued not only ordinary people but

also Umayyad princes such as Khalid ibn Yazid and Abbasid caliphs

such as Abu Ja'far al-Mansur. This

enchantment with alchemy continued until the eighteenth century in

Europe.

The

background, education and culture of Khalid ibn Yazid

Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan was appointed a ruler of Syria in 640 CE. He

became caliph from 661 until 683. This means that he was a ruler in

Damascus during 43 years. The civil administration in Damascus

during this period was in Christian hands and there were naturally

close relations between Muslims and Christians in the caliphate

court.

Abu

Sufian, Mu'awiya's father was one of the leaders of Quraysh. Mecca

was a trading city in close relations with Byzantine Syria and its

inhabitants were notbedouins.

Being raised in a family of merchants, and having spent most of his

life in Damascus as a governor and later as a caliph, Mu'awiya was a

man of culture. He was fond of history. It is reported that after he

had awakened, he sat up and had archives brought to him with the

lives of kings, their history, their wars, and their schemes.

Special pages, who were entrusted with the keeping and reading of

these records, used to read to him. So Mu'awiyah listened every

night to several passages of history, of biography, of annals, and

of political fragments.

These archives and records were kept in the caliphate palace and

constituted a real library, which became a flourishing one along

Alexandrian lines.

Yusuf al-'Ishsh maintains that the first Bait al-Hikma was founded

by Mu'awiya. [42]

Yazid I, Mu'awiya's son, was educated under eminent Muslim scholars.

One of these was 'Ubayd ibn Sharya al-Jurhami (d 67/686) author of Kitab

al-amthal andKitab

al-muluk. Another

scholar was Daghfal ibn Hanzala al-Sandusi al-Shibani (d. 65/684)

who was an expert in genealogy and had written Kitab

al-tashjir on

this subject. He was also versed in Arabic literature and in

astronomy.

It

seems that Mu'awiya saw in Daghfal's scholarship what is required

for the education of Yazid, his son. He

asked Daghfal to go and teach Yazid genealogy, astronomy and Arabic

literature. The scholarship of these two men was reflected on Yazid

so that he was considered one of the noted Arab orators and of their

learned men. He

was a man of culture and a noted poet who left beautiful verses that

are still remembered and cited. He was also an engineer.[43]

Yazid had led the first campaign against the Byzantines in 52/672 in

which several companions of the prophet including Abu Ayyub al-Ansari,

had participated.

Controversy surrounds the biography of Yazid because he was involved

in the tragic wars against al-Husain ibn 'Ali ibn Abi Talib, and Abd

allah ibn al-Zubair. Both of these men claimed the right to become

caliphs after Mu'awiya I, and refused to acknowledge Yazid as a

caliph. The tragic defeat and murder of al-Husain resulted in

deepening the rift between Shi'i and Sunni Islam, and the biography

of Yazid I had been affected as a result. Yazid had no choice in

waging these wars since both contenders wanted to depose him from

his position as a caliph.

Yazid,

was first married to Umm Hisham bint Utba bin Rabiya in 660 and had two

sons, Muawiya

and Khalid, by her. He loved Khalid more,

and was called Abu Khalid, but he made Muawiya,

the elder of the two, his successor.

Mu'awiya II was born on the 28th March 661, on the day when Mu'awiya

I became a caliph. Khalid

must have been born two or three years later.

Mu'awiya II was the first prince of the Ummayyads to grow up

entirely at the court of the Caliph.. He was given private scholars

and teachers. Khalid grew up with his brother and had received the

same education.

When

Mu'awiya II the brother of Khalid ibn Yazid died at about 22 years

of age, Khalid was about 20 years. Mu'awiya II did not nominate a

successor.

The

personality of Khalid ibn Yazid according to Arab historians

Historic and other Arabic sources give accounts full of praise and

appreciation for Khalid. Due to limitation of space we shall give

only the account of Yaqut al-Hamawi in Kitab

mu'jam al-udaba', (Dictionary

of Men of Letters) [44]. Al-Hamawi

writes:

"Khalid ibn Yazid ibn Mu'awiya ibn abi Sufian; the Prince Abu Hashim

al-Umawi:

He

was one the men of Quraysh who were distinguished by eloquence,

kindness and courage. He was a great scientist, expert in medicine

and alchemy, as well as a poet.

Al-Zubayr

ibn Mus'ab had said: Khalid ibn Yazid ibn Mu'awiya was known as a

scientist, a sage and a poet.

Ibn

Abi Hatim said: that Khalid was one of second generation of the

Syrian followers of the Prophet (al-tabi'un). He learned the

Prophet's Hadith from his father and from Dahya ibn Khalifa al-Kalbi

, may God be pleased with him.

Several later scholars quoted Khalid on the Hadith (the sayings of

the Prophet). These

include al-Zuhri, al-Bayhaqi, al-Khatib al-Baghdadi, al-'Askari and

al-al-Hafiz ibn 'Asakir. Khalid

was pious and

he used to fast three days in the week, Friday, Saturday and Sunday.

He used to say that he devoted his attention to books. H

was charitable and he was greatly praised.

He

was brave and daring, and there were debates between him and between

'Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan.

Khalid ibn Yazid died in 90 H, some say that he died in 85 H. He was

attended on his death by Al-Walid ibn 'Abd al-Malik who said in his

eulogy: let the Umayyads shed garments on Khalid, because they will

never mourn any one like him."

Khalid ibn Yazid and his translation activity according to early

Arab historians

The

first translation of Greek science into Arabic was initiated by the

Umayyad prince Khalid ibn Yazid. This is reported by

dependable Arabic sources that were close in time to Khalid. One

should have faith in the authenticity and reliability of the Arabic

original sources instead of accepting the assumptions and

conjectures of historian of the twentieth century about Khalid,

especially since we have disproved such assumptions on concrete

evidence.[45]

Some

Arab authorities assume that the failure of Khalid to become a

caliph was behind his devotion to science and to the translation of

scientific works unto Arabic. About this Ibn al-Nadim says:

"Khalid ibn Yazid ibn Mu'awiyah was called the 'Wise Man of the

Family of Marwan'. He was inherently virtuous, with an interest in

and fondness for the sciences. As the Art [alchemy] attracted his

attention, he ordered a group of Greek philosophers who were living

in Egypt to come to him. Because he was concerned with literary

Arabic, he commanded them to translate books about the Art from the

Greek and Coptic languages into Arabic. This was the first

translation in Islam from one language into another." [46]

At

that time the ruler of Egypt was 'Abd

al-Aziz ibn Marwan ,the brother of the Caliph Abd al-Malik. Abd

al-Aziz governed Egypt from 685 to 704, and

he possibly enabled Khalid to achieve his purpose.

Jabir Ibn Hayyan

reported in Kitab al-rahib how

Khalid summoned Maryanus to teach him 'ilm al-san'a.

Al-Jahiz (c. 776–868)

reported in Kitab al-bayan

wa al-tabyin that

Khalid Ibn Yazid was an orator and poet, eloquent, comprehensive, of

sound judgment and extremely well-mannered, and the first (in Islam)

to order the translation of works on astrology, medicine and

alchemy. [47]

Al-Baladhuri

(d. 279/892) reported also about the involvement of Khalid in 'ilm

al-san'a. [48]

Abu-l-Faraj

al-Isbahānī (897-967) mentioned in Kitāb

al-aghānī that

Khalid wasted his time in the pursuit of alchemy.[49] In

al-Aghani we find also an important testimony about Khalid given by

al-Abu’l-Hasan

al-Mada’ini (d. 830) who

attributed it to one of Khalid's contemporaries.[50]

Al-Mas'udi

(d. 345/956) mentioned in Kitab

muruj al-dhahab that

Khalid occupied himself with alchemy and he quoted three verses from

a poem of Khalid on alchemy.

Ibn

Khallikan (d. 1282 A.D.) praises Khalid's scientific skill and

knowledge, which are exemplified by the quality of his writings.

This author also tells us that Khalid studied alchemy with a Greek

monk named Marianos. [51]

Khalid occupies a

high standing among Arabic scientists and alchemists. Al-Biruni

(d, 440/1048) described Khalid as the first Muslim philosopher.[52]

Most

Arabic works on alchemy give citations from his writings and poems

on ‘ilm al san’a (the

Art).

Khalid ibn

Yazid and the Caliph Abu Ja'far al-Mansur- similar addiction to

alchemy

Khalid was an

Umayyad prince and a grandson of Mu'awiya the founder of the

dynasty. When his brother Mu'awiya II died

in 683 CE he was not elected to be a caliph because of his young

age. Having been relieved from the concerns of the caliphate, he

turned his attention to the pursuit of high culture. Alchemy and

astrology were pursued by rulers and dignitaries throughout history.

In Europe the fascination of rulers and the upper classes with these

pursuits lasted until the eighteenth century. At Khalid's time

alchemy and astrology, beside medicine, had the same importance. Ibn

al-Nadim gave the motives of Khalid in pursuing alchemy as follows: "He

was a generous man, for when someone said to him, 'You have

expended most of your energy in seeking the Art,' Khalid replied,

'In so doing I have sought only to enrich my friends and brothers.

I coveted the caliphate, but was unsuccessful.' Now I have

no alternative other than attaining the culmination of this Art, so

that anyone who one day has known me, or whom I have known, will

not be obliged to stand at the gate of the sultan, petitioning or afraid."

About one century after Khalid, the Caliph al-Mansur pursued alchemy

for the same motives. He was also seeking wealth for the benefit of

the caliphate

Because of Khalid's obsession with alchemy, he initiated the

translation movement in the sciences during the Umayyad Caliphate.,

and he left some important works. However, al-Mansur may have

ordered some translations in alchemy also, but during his time there

were already some Arabic translations available. Khalid sought to

master the "Art" himself because he had all the time needed, and

during his search for adepts who can teach him the "Art" he

encountered several charlatans. However, al-Mansur as a caliph

sought the help of all the available alchemists, who proved, no

doubt, to be charlatans also.