History of Science and Technology in Islam

The Arabic Origin of Liber de compositione alchimiae

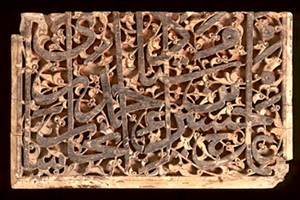

رسالة مريانس الراهب الحكيم للامير خالد بن يزيد

The Epistle of Maryanus, the Hermit and Philosopher, to Prince Khalid ibn Yazid.

|

Liber de compositione alchimiae or the The Book of the Composition of Alchemy is believed to have been the first book on alchemy that was translated from Arabic into Latin. The translator was the Englishman Robert of Chester who was one of the earliest translators to flock to Spain to learn Arabic and to translate some of the Arabic works. He completed his translation on 11 February, 1144.

With the translation of this book, Europe was acquainted to alchemy for the first time. Thus Robert writes in his preface to the translation: “Since what Alchymia is, and what its composition is, your Latin world does not yet know, I will explain in the present book”.[1]

Alchemy remained something rather new to Europe until more than a century later. Thus in 1267 Roger Bacon writes in his Opus tertium (explaining to the pope the rightful role of the sciences in the university curriculum and the interdependence of all disciplines): “But there is another science which is about the generation of things from the elements, and from all inanimate things, …of which we have nothing in the books of Aristotle; nor do natural philosophers know of these things, nor the whole Latin crowd of Latin writers. And since this science is not known to the generality of students, it necessarily follows that they are ignorant of all natural things that follow there from. …And this science is called theoretical alchemy, which theorizes about all inanimate things and about the generation of things from the elements.”[2]

Liber de compositione alchimiae acquired a prominent place in the Latin alchemical literature. The names of Morienus (Maryanus) and Khalid became well known to all alchemists in Europe. Their importance matched that of al-Razi, Ibn Sina and Jabir.

A large number of Latin manuscripts have survived. These were classified into several categories.[3] Five contain the original Latin text that was not altered by later editors. Two of these un-edted manuscripts go back to the thirteenth century. They are the Glasgow Hunterian Library MS 253, 46r-53v, and the Paris Bibliotheque Nationale MS Lat. 7156, 197-201v. They contain the story, as told by Ghalib the mawla (client) of Khalid, of how Khalid and Morienus came to meet each other. This is followed by the dialogue between the two.

All the other numerous manuscripts contain a revised dialogue. Some contain a preface by Robert of Chester, and some have an additional speech by Morienus. The various parts were printed for the first time in 1559 in Paris. The printed edition contains the preface of Robert of Chester, the speech of Morienus, the revised account of Ghalib, and the revised dialogue. The Latin title translates as:” Booklet of Morienus Romanus, of old the Hermit of Jerusalem, on the Transfiguration of the Metals and the Whole of the Ancient Philosophers’ Occult Arts, Never Before Published”.[4] The same publisher issued a second edition in 1564. The text was printed in 1572 in a larger collection of alchemical texts published in Basel.[5] The Latin printed edition was translated into English, German and French.

The first English translation was done in the seventeenth century and is contained in a manuscript in the British Library, MS Sloane 3697. This is a translation of the Paris Latin edition of 1564. This translation was first published by Holmyard in 1925 [6] . A recent edition in current English was published by Adam McLean in 2002. [7]

In 1974 an English translation based on the oldest unrevised Latin manuscripts was undertaken by Lee Stavenhagen who published the Latin text on opposite pages to his translation.[8]

As is customary with most historians of alchemy of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such as Berthelot and Ruska, doubts were cast on the old established knowledge about the translated Arabic works into Latin. Thus the Latin works of Jabir were considered to be authored by a Latin Pseudo-Geber. The Morienus-Khalid dialogue did not escape a similar kind of judgment. Ruska who was a master in the art of considering most works to be written by pseudo authors, cast doubts about Robert of Chester’s translation and on Khalid, Morienus and their dialogue, and he came out with the conclusion that the whole Latin work was a compilation of an Italian Christian cleric possibly as late as the fourteenth century. Other scholars followed Ruska in this assumption.[9]

The curious thing is that Ruska knew about the existence of several citations in Arabic alchemical literature extracted from the Maryanus--Khalid dialogue, but this did not deter him from coming out with his conclusion. The Italian compiler, he assumed, should have known Arabic and he had interpolated some Arabic citations. Ruska did not know as yet about the existence of the complete Arabic texts. This stresses again the fact that historians of science, however eminent and scholarly they are, should not come up with sweeping conclusions on the basis of the limited Arabic sources available to them.

Although Stavenhagen was also skeptical about Robert of Chester and his Latin translation, yet he became convinced that the work was “certainly a translation from Arabic”. He arrived at his conclusion after he saw Holmyard’s translation of The Book of Knowledge Acquired Concerning the Cultivation of Gold العلم المكتسب في زراعة الذهبof Abu al-Qasim al-`Iraqi. [10], and by the mention of Maryanus and Khalid in the commentary of Ibn Umayl on Kitab al-ma’ al-waraqi wa al-ard al-najmiyah.[11] Stavenhagen did not know about the existence of the complete Arabic manuscripts of the Maryanus-Khalid dialogue.

There is no doubt about Khalid’s place in the history of the Umayyad Caliphate. Ruska and others doubted whether he has engaged himself in alchemy. Sezgin gave enough historical evidence testifying that Khalid did actually work on this science.[12] His relationship with Maryanus was told by Jabir in Kitab al-Rahib,[13] and citations from the dialogue were given by most succeeding Arab alchemists, such as Ibn Umayl (10th century).

In 1971 Sezgin’s volume IV was published. It indicated the existence of complete Arabic manuscripts of the Maryanus Khalid dialogue.[14] Similarly in 1972 Manfred Ullman’s Die Natur und Geheimwissenshaften im Islam was published giving also similar information about the complete manuscripts.[15] Both furnished information about other Arabic works that gave citations from the dialogue.

Thus the question of the Arabic origin of the dialogue was settled. It was deemed necessary, however, to edit and publish the Arabic text and correlate it with the Latin translation.

The present work aims at this. The writer had sought to obtain copies of the two known Arabic manuscripts from the libraries of Istanbul, and he was fortunate to receive help.[16] These are Fatih 3227 (fol. 8b-18b) and Şehit Ali Pasha 1749 (fol. 61a-74b). The arrival of the copies made this work possible. The writer was able also to secure copies of several Arabic manuscripts that gave citations from the Maryanus-Khalid dialogue. Appendix 1 gives a list of the Arabic sources that were available for this study, and a list of the manuscripts that were not available. It is believed that more Arabic sources may appear in future.

The Arabic texts of Fatih and Şehit Ali Pasha are similar to each other with minor differences. Fatih was taken as a base, and an edited text is now ready. There remains a review of the citations in the various other works. The largest citation is the in Kitab al-shawahid fi al-Hajar al-wahid, in BL MS add 23418. It was found that the text in this MS has been revised so that it deviates to some extent from that in Fatih and Şehit Ali Pasha.

The texts in Fatih, Şehit and BL were compared with the two English translations mentioned earlier. It was found that the translation of Stavenhagen corresponds very well with the Arabic text of Fatih and Şehit. This result seems understandable because Stavenhagen opted to translate the oldest un-revised Latin text, whereas the seventeenth century English translation published by McLean is based on the revised Latin text that was printed in Paris in 1564.

The English translation of Stavehagen and the Arabic text start with Ghalib’s account and contain the dialogue. The Speech of Morienus is not part of the Arabic text nor of the earliest un-revised Latin text that was translated by Stavenhagen.

The last pages of the English translation are not found in the Fatih and Şehit manuscripts. Search will continue to find the possible Arabic texts that correspond with these.

The account or prologue of Ghalib is reproduced at the end of this article. It shows the correlation between the Arabic text and the English translation. The page numbers of the Stavenhagen translation are given so the reader can consult also the Latin text that faces the English one. The important deviations between the Arabic and the English are indicated. The endnotes show the distortion of the Arabic names. There must have been errors in the Latin translation due to some ambiguity in the Arabic text or of lack of understanding it. There is also in some places a purposeful editing while the translator was undertaking his work. These will become apparent to the reader.

The writer did not deem it necessary at this stage to make a new translation of the Arabic text, but the reader who knows Arabic will be able to see how closely and remarkably the English translation correlates with the Arabic original.

Appendix I Arabic texts of the Maryanus –Khalid dialogue

I- Available a- Complete manuscrıpts 1- MS Fatih 3227 (fol. 8b-18b) 2- Şehit Ali Pasha 1749 (fol. 61a-74b) b- Large cıtatıon 3-Brıtısh Lıbrary MS add 23418, al-Shawahid fi al-hajar al-wahid (fol. 123a-125b) c-Fragments 4-al-`Iraqi al-Simawi, al-`ilm al-muktasab, BL MS add 24016, (fol. 27; 28,; 48) 5-al-Gildaki, Nihayat al-talab II, Berlin, MS 4184, (fol. 183) 6 Manuscript of Abdallah Yurki Hallaq,Aleppo, (p.180). 7-NLM (National Library of Medicine), Wahington, MS A-70 (fol. 53b-57b) II- Existing but not available at the time of writing this paper 8- Khanji , Cairo, according to Kraus, Jabir, vol. I, pp. 182. Sezgin, p. 126, (Seems to be a complete one) 9- Haidarabad, Asafiya , according to Stapleton. See Sezgin, p.111. 10-Teheran, Khaniqah-i- Ni'matallah 145 (a fragment, 18b) Sezgin, p. 126. 11-Leningrad University, MS Or. 1192, Sezgin, p.126 12 as-Sifr al-mubajjal, s. Siggel KataI. Gotha p. 65. , see Ullman, p. 193, note 2. 13-al-Iraqi al-Simawi, K. al-Aqalim al-sab`a, s. Siggel Katal. Gotha p. 25; see Ullman, p. 193, note 2. 14- Chester Beatty MS 5002, (fol. 55a). see Ullman’s Catalog, p. 172 15-Personal Collection- see Kraus I, p.187. [1] McLean, Adam, The Book of the Composition of Alchemy.Glasgow, 2002. p.5 [2] Roger Bacon, quoted by John Maxson Stillman, The Story of Alchemy and Early Chemistry, Dover, 1960. pp. 262-263 [3] Stavenhagen, Lee, A Testament of Alchemy, The University Press of New England, Hanover, New Hampshire, 1974, pp. 53-54, and appendix 1. [4] Morieni Romani, Quondam Eremitae Hierosolymitani, de transfiguratione metallorum et occulta, summaque antiquorum philosophorum medicina, Libellus, nusquam hactenus in lucem editus. Paris, apud Gulielmum Guillard, in via Iacobaea, sub diuae Barbarae signo. 1559. [5] Pernam, Petrus (ed), Auriferae artis, quam chemia vocant, antiquissimi authores, sive Turba Philosophorum, Basilea, 1572, 2 vols. [6] Holmyard, Eric,, “A Romance of Chemistry”, a series of articles that appeared in Chemistry and Industry, Part I, Jan. 23, 1925, pp.75-77; Part II, Jan. 30, pp.106-108; part III, March 13, 1925, pp.272-276; Part IV, March 20, 1925, pp. 300-301; Part V (printed IV by error), March 27, 1925, pp.327-328. In this series of articles Holmyard published the full text of the seventeenth century English translation of Ye Booke of Alchimye, (Sloane MS. 3697), [7] McLean, op.cit. [8] Stavenhagen, op. cit. [9] McLean,op. cit. p. 3; .Ruska, Julius, Arabische Alchemisten, Wiesbaden, reprint, 1967, p.48. [10] Holmyard, E. J., Abu 'l-qasim Muhammad Ibn Ahmad AI-'Iraqi. Kitab al-'ilm al- muktasab fi zira'at adh-dhahab; book of knowledge acquired concerning the cultivation of gold; the Arabic text edited with a translation by E. J. Holmyard. Paris: Geuthner, 1923.. [11] Stapleton and Husain, Three Arabic Treatisies on Alchemy by Muhammad Bin Umail, Texts edited by M. Turab, Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta 1933, pp. 54, 84. [12] Sezgin, Fuat, Geschichte des arabischen Schriffums,Vol. IV, Brill, 1971,. pp. 120-125 [13] Mukhtarat Jabir ibn Hayyan, edited by Paul Kraus, Cairo, 1935, p. 529. [14] Sezgin, op. cit.,, pp. 111 and 126, and the Arabic updated version, Jeddah, 1986, pp. 163 and 188. [15] Ullmann, Manfred, Die Natur und Geheimwissenshaften im Islam, Leiden, 1972, pp. 192-193 [16] . Professor Fuat Sezgin came up to help without delay and the present work is indebted to his unfailing support. He sent me copies were on CD-ROM which was an invaluable help in editing the Arabic text. After Professor Sezgin’s quick support, IRCICA in Istanbul sent later another copy on microfilm. [17] The title of the Arabic treatise is: The Epistle of Maryanus the Hermit the Philosopher to Prince Khalid ibn Yazid. [18] This is a translation of the Muslim verse that precedes the start of any text. بسم الله الرحمن الرحيمThe word Lord is the cleric word for God. [19] The names of Khalid, Yezid and Mu`awiya were distorted in the various Latin manuscripts. See Lee Stavenhagen, p. 2, footnotes 1 and 2. [20] Ghalib was a mawla and not a servant. A Mawla is a non-Arab Muslim. In the early days of the Arab conquests a Mawla chose sometimes to associate himself with an Arab dignitary and to become one of his followers.. [21] Arabic Rumi, is not Greek from Greece, it denoted a person from Asia Minor or Anatolia. When Anatolia became Muslim the word Rumi became a surname of a Muslim from that country ( e.g. Ibn al-Rumi).During the Umayyads Asia Minor was still Byzantine and so Morienus was a Christian Byzantine from Asia Minor.. [22] Dirmanam is a distortion of Dayr Murran, see note below [23] Major work is al-san`a in Arabic الصنعة In the later Latin revised versions the word Magistery was used. [24] Dayr Burran is most probably Dayr Murran in Damascus. It was on the lower slopes of Jabal Qasyun, overlooking the orchards of the Ghuta. It was a large monastery, and around it was built a village and, one presumes, a residence in which the caliphs could both entertain themselves and keep watch over their capital. Dayr Murran often figured in poems of the time. The caliph Yazid I (father of Khalid) was staying there sometimes. Other caliphs and their representatives visited or lived there on various occasions. (Soudrel, E.I. under Dayr Murran). Khalid, according to this text, used to stay sometimes at Dayr Murran as well. [25] Khalid was not a king because he did not become a caliph after his father Yazid. In the Arabic text he is called amir or prince. [26] The Arabic name is Hiraql, hence the various Latin ditorsions. [27] The Arabic text says: God help us in dealing with him because he is a wily man despite his old age. The Latin translator edited this Arabic sentence. [28] The Arabic text makes Maryanus call Khalid by his name “Khalid” without any formality, whereas in the Latin text Morienus is addressing Khalid as “O, King” [29] This is the first question of the Morienus-Khalid dialoge. |

Copyright Information

All Articles and Brief Notes are written by Ahmad Y. al-Hassan unless where indicated otherwise.

The design of this website does not belong to Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, the design was based on common webdesign elements.

All published material are the copyright of the author (unless stated otherwise) and may not be published or reproduced in part or in whole without the express written permission of the author.